Use evidence from the Romeo And Juliet and:

One of the sources below

Underline your thesis statement.

Have clear topic sentences.

Use the five-paragraph essay format.

Romeo and Juliet Essays V2

Lois Kerschen

Kerschen is a freelance writer and adjunct college English instructor. In this essay, Kerschen considers whether fate, the personal characteristics of Romeo and Juliet, or the demands of justice determine the outcome of the story.

Whenever a tragedy occurs, people want to know what went wrong. They look for the causes, the reasons for the end result. With Romeo and Juliet, the opinions have varied as literary criticism has taken different viewpoints through the years. Since William Shakespeare named the play for the two central characters, the immediate reaction is to look at them for fault. However, Shakespeare is never that simple, so a deeper analysis is warranted.

The great German Shakespearean critic, August von Schlagel, blamed fate for the tragedy, but in the sense that the cruel world is too terrible a place for a love as tender as that of Romeo and Juliet. Instruction books such as Kelley Griffith’s Writing Essays about Literature very matter of-factly blame fate as well by telling students that “if the plot is only part of a larger or ongoing story, then the characters are more likely to seem at the mercy of forces beyond their control.” Therefore, since the plot of Romeo and Juliet is actually only one episode of a long feud, the young couple, according to Griffith, “cannot escape the undertow of their families’ history.” Even the powerful prince cannot prevent the tragedy, although he tries, because Romeo and Juliet are identified by fate as “star-crossed” and “death-marked.”

It must be noted that the family feud is the reason that Romeo and Juliet’s relationship is a “forbidden love.” It should also be noted that the play begins with a fight scene bet of the two families and ends with a peace agreement between Lords Montague and Capulet. The family feud could then be seen as a bookend structure around the lovers’ story. Shakespeare did not create the story-he inherited it. The feud is part of the previous versions that he draws upon, in which the feud serves as a complicating device that keeps the lovers apart. How the feud first and last in the play, that is, in the most attention-getting spots for the audience, indicates that the feud is the most important facet of the story. Although this play is considered one of the greatest love stories of all time, viewed from another angle, it may be that it is a story about hate; a story that is the final episode of a long-running saga. The love affair of Romeo and Juliet may be only a device to bring about an end to the feud and show how terrible the consequences can be of such violent and vindictive behavior. As a result, the blame according to this theory can be placed with the demands of justice.

Further support for this interpretation is the realization that violence runs throughout the story, linking each event. Romeo meets Juliet at the Capulet party but his presence there fuels Tybalt’s challenge to him the next day. That challenge leads to the deaths of Mercutio and Tybalt. That violence is the reason that Romeo is banished. His banishment leads to the risky ruse of Juliet’s death, which leads to Romeo coming to Juliet’s family tomb. There, the family feud causes Paris to assume that Romeo has evil intent and the resultant fight costs Paris his life. The entrapment and despair that the feud has precipitated next results in the death of both Romeo and Juliet. With these events in mind, it would be easy to see this play as being about the feud, not the lovers. After all, Juliet says, “My only love sprung from my only hate!”

Many studies of the play remark on the relationship of love and hate. Could Juliet’s love spring

from hate because they are both intense passions? A nineteenth-century German scholar, Hermann Ulrici, said that the love of Romeo and Juliet had an ideal beauty but was condemned from the beginning because of its “overpowering and reckless” passion that disturbs “the internal harmony of the moral powers.” Ulrici concluded that Shakespeare brings balance back to the situation through the deaths of the couple and the end of the feud. Following this interpretation, Denton Snider, an American scholar, later agreed that Romeo and Juliet are destroyed by their own love. He said that, just as with the passion of hate, the intensity of love’s passion blots out reason and self-control and leads to destructive behavior. Snider also thought that there was a moral justice involved in that the fire of love that consumes Romeo and Juliet is the fire of

sacrifice that is rewarded with peace between their families. Snider writes, “The lovers, Romeo and Juliet, die, but their death has in it for the living a redemption.”

So, the argument comes back to the idea of justice. In 1905, American scholar Stopford Brooke wrote that the feud is the central event and cause of the tragedy and that the accord reached at the end was the goal of justice. Brooke counsels that discussions of fate as a determinant in the story would be more correct if the name “Justice” were given to fate.

While Brooke and others reject the mere happenstance of fate for the more intentioned aim of justice, the conclusion is still that outside forces bring Romeo and Juliet to their doom. Another slight turn of the viewpoint sees justice as a moral lesson. In this light, there is the unsympathetic view that Romeo and Juliet are foolish children who are inevitably headed toward ruin because they do not consult or gain the approval of their parents for their marriage. Once again, the sentiment is that passion leads to head-strong, reckless behavior such as a refusal to obey constituted authority (one’s parents, one’s ruler). This results in a disruption of hierarchical order, and the tragedy works to reestablish that order through loss and grief. One’s attention is drawn to the two central figures, and a quite natural reaction is that Romeo and Juliet are impetuous kids. In that case, this story can be interpreted as having a more universal message about young love and not just about the two young lovers in the play. Undoubtedly, it is the universality of Shakespeare’s dramas that has made them classics, so perhaps Shakespeare’s intent was not just to tell a story, but to give an example. If the theme were not timeless, then Leonard Bernstein might not have taken the story and transformed it into West Side Story. There are foolish teenagers in every generation, and there is senseless feuding in every culture.

Although it has been suggested that the love of Romeo and Juliet was too ideal to survive in this imperfect world, it would seem a shame to think of true, passionate love inevitably leading to a bad result. Perhaps the problem is not with the intensity of the emotion, but the inability to control and direct that emotion in a positive way. If that is the case, then Romeo and Juliet are doomed, not by the fates, not by the judgment of justice, but by their own character flaws. Shakespeare may have altered the classic form of the Greek tragedy, but that does not mean that he totally ignored the Greek formula for the tragically flawed hero.

It can be said that part of Romeo’s character flaw is that he believes in the fates and therefore feels powerless to help himself. He has a bad feeling that going to the party may lead to eventual doom, but he goes anyway. He surrenders himself to the guidance of the gods not just out of piety but perhaps because he shirks responsibility. Killing Tybalt is a rash act that needed not

have happened if Romeo had been better able to control himself. Instead, Romeo succumbs to an irrational and violent reaction and then feels sorry for himself as “fortune’s fool” who has been pushed by fate into committing the terrible deed.

Juliet’s nature is more practical and cautious, but her innocence and the intensity of her love are her downfall. Moreover, she lives in a family where her father does not know how to express his love except to make decisions for Juliet that he thinks are in her best interest. Her mother is too cold and distant to give her good advice, and her nurse, though she loves Juliet, is too crude to understand the delicacies and dangers of first love. Consequently, Juliet is not chastised by the critics as much as Romeo for being rash. As a young girl practically restricted to her house by the social customs of her time, she has very little control over anything anyway. Romeo, however, is older and has slightly more autonomy.

Is it fate, a need for justice, or the characters themselves who bring a tragic end to Romeo and Juliet? Can it be a combination of all these factors? They seem to be inextricably mixed, despite the efforts of the critics to separate them. Ben Jonson and many others have admitted to Shakespeare’s genius, even though they found other faults in his work. Scholars have commented on the depth of Shakespeare’s understanding of human nature and the psychological aspects of his plays. Is it not possible, then, the Shakespeare was smart enough and sensitive enough to have picked up on all the nuances of a human situation and been able to incorporate highly complex emotions and interactions in Romeo and Juliet ? Shakespeare was aware of the conventions of his time and the expectations of his audience for certain elements of tragedy. But he was also innovative enough to blend some of the traditional aspects of tragedy with a much more intricate and multi-faceted dramatic structure that included an amazing depth of

characterization. There is a reason that Shakespeare is considered the greatest dramatist of all time, and that reason may be that he was able, better than anyone else, to fill his plays with a richness that, four hundred years later, had scholars still mining its depths.

Source:

Lois Kerschen, Critical Essay on Romeo and Juliet, in Drama for Students, Thomson Gale, 2005.

Bryan Aubrey

Aubrey holds a Ph.D. in English and has published many articles on Shakespeare. In this essay, Aubrey discusses two film versions of the play.

Romeo and Juliet has always been one of Shakespeare’s most frequently performed plays. However, since the late 1960s, many more people have become familiar with the play through movie versions than through live performances in a theater. Franco Zeffirelli’s lush Romeo and

Juliet (1968) has proved enduringly popular. In 1996, Baz Luhrmann’s frenetic William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet was a big box-office hit for the Australian director.

The challenges faced by a director who wants to make a film of a Shakespeare play are immense. Not too long ago, Shakespearean purists rejected the very idea of filming Shakespeare. Shakespeare appeals to the ear, they said, whereas the cinema appeals to the eye, so there is a

natural antipathy between the two forms. Film favors action, whereas in a Shakespeare play

acters often give long speeches. These “talking heads” can be effective on stage, but filmgoers, conditioned by the conventions of the medium, become impatient or bored with them. The film director must therefore cut the original text considerably. Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet, for example, contains only a third of the original text, and Zeffirelli was roundly criticized by some Shakespeare scholars for the drastic nature of the cuts, as well as for shifting lines within scenes and occasionally adding a line or half-line of dialogue. The critics complained that Shakespeare was not a hack screenwriter whose work could be chopped up and rearranged at will. But others noted that Zeffirelli had shown himself to be a master of his craft because he was able to compensate for the omitted text by recreating it visually.

Zeffirelli’s stated intention was to popularize Romeo and Juliet by bringing it to a mass audience. With this goal in mind he decided to cast two young and unknown actors in the title roles. This was a break with tradition since Shakespeare’s lovers were usually played by more experienced actors. In a 1936 film version, Norma Shearer, who was 36 years old, played Juliet, and Leslie Howard, 46 years old, played Romeo. In the play, Juliet is barely fourteen years old, and Romeo not much older. So, Zeffirelli chose Olivia Hussey, age fifteen, to play Juliet and Leonard

age seventeen, to play Romeo. Although older, more experienced actors might have been better able to deliver the lines, they would have found it hard to convey the extremePage 263 | Top of Articleyouth and innocence of the protagonists, which is central to the play and its repeated contrasts of youth and age.

Zeffirelli’s film begins with a sober off-screen reading of the prologue by Sir Laurence Olivier as the camera pans across Verona as seen from high above. (Zeffirelli was a great admirer of Olivier’s work and this was a deliberate reference to the opening of Olivier’s 1944 film of Shakespeare’s Henry V.) The film then cuts to a busy, noisy, market square, and a wealth of visual detail piles up as the camera pans. It is clear from the beginning that this will be a spectacular film, one in which the setting itself becomes—as Zeffirelli believed it should—like a character in the action.

Although Zeffirelli was forced to cut much of the text, he succeeded in creating visual images that effectively convey Shakespeare’s verbal images and themes. This can be seen from two examples, the first of which comes right at the beginning of the film. When the two Capulet servants enter, the camera shows only their legs, clad in tights, and their crotches, which display prominent codpieces. This image replaces the aggressive sexual talk in this scene in the play, After the initial sword fight, the sword-wearing Tybalt enters in a similar codpiece-emphasizing shot. The audience is being invited to identify male sexual energy and pride with the violence that pervades the play.

Interestingly, Zeffirelli does not present Romeo in this way. Faithful to Shakespeare’s text, his Romeo is more contemplative, even dreamy, and unwilling to fight until his friend Mercutio is killed. Then, he gets dragged into the cycle of violence. Feminist readings of Romeo and Juliet often emphasize this point, arguing that the tragedy results not from the workings of fate, which is the traditional view of the play, but because of the rigidity of the male-dominated social order that Romeo at first resists but that eventually overwhelms him.

The second example of how visual imagery can present verbal themes occurs at the Capulet ball, as Jack Jorgens notes in his book Shakespeare on Film. At first, the dancers form two separate circles. After Romeo has set eyes on Juliet and joined the dance, the dancers form two concentric circles, with Romeo in the outer circle and Juliet in the inner one. This might seem on the surface to be an image of harmony, but it should be noted that the circles are moving in opposite directions—a clear allusion to the theme in the play of the inextricable linking of the opposites of love and hate, unity and separation.

Another highlight of Zeffirelli’s film, and an example of how he makes up for textual cuts with visual treats, is the long duel sequence between Mercutio and Tybalt. This not only makes gripping cinema but also gives the director a chance to further characterize Mercutio and Tybalt. Killing Mercutio seems to have been the last thing on Tybalt’s mind, and Mercutio’s death is made even more poignant by the fact that right up to the end, his friends think it is just one more of his jokes.

The purists may have groaned at some of Zeffirelli’s methods, but he was certainly vindicated at the box-office. The film became a worldwide success. It has been called a film for the 1960s, and indeed it did succeed in capturing the zeitgeist of those turbulent times of “flower power,” sexual freedom, and anti-Vietnam war protests. The brief shot of the lovers nude anchors the film in that uninhibited sixties era, as does the very first shot of Romeo walking toward the camera carrying not a sword but a flower. “Make love not war,” one of the slogans of the sixties counter-culture, is the subtext here.

If Zeffirelli’s was a film for the sixties, Luhrmann’s William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet was squarely aimed at the youth culture of the 1990s. The film begins (and also ends) with a shot of a small television in the middle of the darkened screen. On the television, a female news anchor reads the prologue as if it were a news item. This is a very different world than that revealed in the stately prologue read by Olivier in Zeffirelli’s film. An off-screen male voice then repeats the prologue as a montage shows the main characters, and some of the words even appear on screen as well, as headlines in newspapers. The director clearly wants to ensure that the audience understands every word of the Shakespearean verse.

The film then leaps into the hot, combustible world of Verona Beach, with its feuding families and family-loyal gangs. Both the Capulets and Montagues appear to be gangland bosses dealing in real estate or construction, and their gun-toting minions, pumped up with testosterone, drive around town in convertibles, looking for trouble. The guns bear the brand name “Sword,” thus neatly making sense of the Shakespearean text when the mayhem breaks out.

The opening sequence sets the pace, the camera keeps moving, and it hardly lets up throughout the film. Nor does the soundtrack, a mix of pop and classical, in which hip-hop bands such as Garbage and Radiohead rub shoulders with Mozart and Wagner.

As a director, Luhrmann is inventive and willing to take risks, which give the film an admirable freshness. He certainly has some fun with the Capulets’ ball, creating it as a fancy dress extravaganza in which Mercutio is a high-stepping drag queen, Lady Capulet a comic turn, and poor Juliet a winged beauty stuck with the eager but inane suitor Paris, whose picture is shown,

in a nice touch of directorial wit, on the front cover of Time magazine as “Bachelor of the Year.” When Juliet escapes for a mom

s for a moment, she and Romeo gaze at each other through a fish tank.

Leonardo DiCaprio, selected for his appeal to teenagers, is an adequate, even charming Romeo who speaks the verse reasonably well, but it is Claire Danes’s Juliet who leaves the deeper impression. She is a more mature, expressive and articulate Juliet than Olivia Hussey in the 1968 film. Her face registers a range of emotions with impressive subtlety. Danes conveys Juliet’s practical nature, and she seems older than Romeo, even though this is not the case. DiCaprio’s Romeo is a romantic and a dreamer. In both cases, this is quite true to Shakespeare’s play.

Luhrmann also exercises his creativity in the traditional balcony scene, in which Romeo and Juliet first pledge their love. This Romeo, like every other Romeo for four hundred years, spies a light at the window and thinks he sees Juliet, but then who should poke her head out of the window but the disapproving Nurse. Meanwhile, Juliet just happens to be taking the elevator downstairs, and when the two finally meet face to face outside, she is so surprised she falls backwards into the swimming pool, taking Romeo with her. The scene that follows has all the innocent appeal that the text demands.

Like Zeffirelli, Luhrmann manages to convey Shakespeare’s themes through some startling visual effects. In this all-action, quick-cutting movie, which was aimed at the supposedly short attention spans of teens, there are nonetheless two moments of utter stillness. The first is when the lovers are shown lying asleep together, and this foreshadows the moment they lie together in death at the end. The position of their bodies, with Juliet’s right arm draped over Romeo’s midriff, and both heads turned to the right, is almost exactly the same in both shots. As in the

Shakespearean text, love and death are intimately, tragically, linked.

In the death scene, Luhrmann makes a dramatically effective innovation. Juliet shows signs of life several times as Romeo prepares to take the poison. He is looking elsewhere and fails to see her. Then, just as he downs the fatal mixture, Juliet wakes up fully, smiles and touches him on the cheek. It is too late, but Juliet utters her last speech, beginning “What’s here?” while Romeo still lives, and he is still alive as she kisses him, hoping that some drop of poison is left on his lips that will dispatch her too. Romeo’s final line, “Thus with a kiss I die,” is spoken to a conscious, anguished Juliet, about a kiss initiated by her, not, as in the text, by Romeo on the lips of a Juliet he believes to be dead.

In the cutting of the text, Luhrmann makes different decisions than Zeffirelli. Luhrmann gives more insight into Romeo’s state of mind at the beginning of the film. As in Shakespeare’s play, Romeo is stuck in love-sick melancholy, pining for a woman named Rosaline who apparently scorns him. This is omitted in Zeffirelli’s film, with the result that some of Romeo’s lines after he has met Juliet are deprived of their full meaning. Luhrmann includes the scene in which Romeo buys poison from an old apothecary (omitted in the Zeffirelli film, which does not explain how Romeo acquired the poison). Both films omit the incident at the end of the play where Romeo kills Paris, presumably because neither director wanted the hero to have too much blood on his hands. Neither filmmaker fully brings out the reconciliation of the families at the end, although this is clearly announced in the prologue.

But carping over inevitable textual cuts should not obscure the fact that both Zeffirelli and Luhrmann brought a freshness of vision to a four-hundred-year-old play, translated it into a new medium, and in each case won for Shakespeare’s tragic story a new generation of enthusiastic admirers.

Source:

Bryan Aubrey, Critical Essay on Romeo and Juliet, in Drama for Students, Thomson Gale, 2005.

Douglas Dupler

Dupler is a writer and has taught college English courses. In this essay, Dupler examines the concept of romantic love as it appears in one of the greatest love stories of all time.

The main characters of Romeo and Juliet are young “star-crossed” lovers who experience a love that lifts them into ecstatic extremes of emotions for a few days and then leads them to a tragic ending. The idea of love that appears in this play, that a certain type of romantic love can make people willing and able to transcend boundaries and constraints, has lived in Western literature for many centuries. The power of this idea of love has fueled the imaginations of readers and theater audiences for generations. For Romeo and Juliet, this type of love pits them against their parents and against their society, against their friends and confidants, and creates conflict with their religious leader. Their love ultimately brings them the possibility of exile and then helps to bring about their death. At the same time, their experience of love gives each of them the strength and desire to pursue their love against the odds and makes them willing to die for love. Although the play happens in the span of less than one week, both main characters undergo much change. In the end, the death of the young couple heals a longstanding rift between their families. In this play, romantic love is portrayed in a way that reveals its power and complexity; this love is at once invigorating, destructive, transformative, and redemptive.

In the beginning of the play, Romeo is heart-broken over a young lady, Rosaline, who does not return his affection. He is gloomy and withdrawn and claims that he is sinking “under love’s heavy burden.” Romeo at first describes love as a “madness” and as a “smoke raised from the fume of sighs.” Romeo’s friends, who wish to see him lifted above his melancholy, urge him to stop philosophizing about his lost love and to seek another young lady as a new object of his affections. Benvolio urges Romeo to heal himself of love’s despair by “giving liberty unto thine eyes.” Mercutio does the same when he tells Romeo to lessen his sensitivity and to “be rough with love.” When Romeo meets Juliet, his vision of love changes profoundly. Later, Friar Laurence acknowledges this change when he remarks to Romeo that his feelings about Rosaline were for “doting, not for loving.”

At the same time Romeo is dejected about unfulfilled love, Juliet, not quite fourteen years of age, is being urged by her nurse and her mother to consider marrying Count Paris. For both of these older women in Juliet’s life, what matters most is a socially advantageous marriage, and this marriage is being arranged before Juliet has even seen her suitor. Juliet, however, seems to intuit

that this type of pairing will not sustain her; she promises her guardians that she will view, but

may not like, her arranged suitor. Already, for both Romeo and Juliet, there is a sense that there

beyond the common, that is special and worth patience and suffering

nn

Then comes the scene in which Romeo sees Juliet for the first time. He is instantly enamored and entranced, and his melancholy and despair are quickly transformed. Not long before, Romeo had been speaking of Rosaline’s charms but upon seeing Juliet, he claims he “ne’er saw true beauty till this night.” From the beginning, there is also something ephemeral and impractical about this love. Romeo sees a “beauty too rich for use, for earth too dear.” For Juliet, this sudden love is complicated as well, and she exclaims, “My only love, sprung from my only hate.”

The romantic love between Romeo and Juliet occurs with a glance and enters them through their eyes. This is rich symbolism. First, romantic love in this way becomes individualized and has nothing to do with cultural constraints or the advice of mentors. This love seizes the couple with a recognition that seems to go beyond them. This “passion lends a power” that awakens each of them and energizes them. For Romeo, this awakening increases his sense of beauty and his feelings for the world as evidenced in his poetic declarations to Juliet. Romeo’s language overflows with a sudden awareness of the beauty of the world and the new importance that has been added to his life. Romeo resolves that even “stony limits cannot hold love out.” In addition to the enticements of the attraction, each lover feels a danger in this type of loving. Romeo later states to Juliet that “there lies more peril in thine eye” than twenty swords, while Juliet worries that their love is “too rash, too unadvised, too sudden.”

For Juliet, this new feeling strengthens her against the cultural forces that would deny her love and freedom. She pledges that she would “no longer be a Capulet” if such denial would be necessary to sustain her love. Juliet’s new feelings of love awaken her to the difficulties of her situation as a young woman in her culture. It is a rough and male-dominated culture. From the beginning, minor characters bicker and threaten violence, with one serving man declaring that women are the “weaker vessels” and another one bragging about “cruelty to the maids.” It is a world of long-standing feuds and quick aggression. The friar, or the religious authority, at one point refers to fear as “womanish” and tells Romeo that his tears, or his emotional feelings, are “womanish,” implying a disrespect for both the feminine and for Romeo’s romantic feelings. Theirs is a world where Juliet’s kind of strength is not honored, as when Friar Laurence tells Romeo, “women may fall when there’s no strength in men.”

Juliet struggles to honor her feelings of love for Romeo. Her closest friend in the play, the nurse, argues against Juliet’s love for Romeo and tries to convince her to consider the arranged marriage with Paris. The nurse tells Juliet, “you know not how to choose a man,” capitulating to the demands of male authority rather than to the demands of the feminine heart. Juliet also faces tremendous pressure from her parents, who will not allow her individuality and freedom when it comes to considering marriage. Her father uses despicable and shaming language when trying to force her to marry Paris. He threatens to exile her to the streets, calling her “unworthy,” “a curse,” and a “disobedient wretch.” In keeping with the patriarchal arrangment of power, Juliet’s father treats Paris with respect and deference. Later, Capulet denigrates Juliet’s freedom of choice by referring to it as a “peevish self-willed harlotry.” Knowing her place in this society, Juliet’s mother refuses to make a stand for her daughter’s freedom, pressuring her to accept her father’s demands. Juliet despairs over this outward pressure, wondering why fate was so hard on

“so soft a subject” as herself. Finally, the force of love prevails within Juliet. Although outwardly she denies her truth and agrees to marry Paris, inwardly she knows that her love for Romeo has given her intense resolve, or the “power to die” if necessary.

Romeo also struggles with the harshness of the world around him. When Romeo is at his most vulnerable and emotional, his friends urge him to quickly move out of his moodiness into the world of action. For Mercutio, love is nothing more than a “fine foot, straight leg, and quivering thigh.” Even Romeo doubts his new feelings of peace and reconciliation that his love for Juliet has brought to him. After Romeo’s failed attempt to make peace with Tybalt, Mercutio is slain, and Romeo is unable to remain in his peaceful state. Referring to Juliet, he shouts, “Thy beauty hath made me effeminate.” This failure to respect the “effeminate” feelings he experiences with Juliet is Romeo’s undoing; when he slays Tybalt in an uncontrolled rage, he sets into motion the tragic ending of the story.

Romeo is not the only character who cannot fully transform or overcome the side of his nature that betrays or fails to support the noble qualities of romantic love. Several characters in the play add their parts to the tragic ending. Mercutio, despite Romeo’s peaceful influence, stirs up the fight scene in which he is slain and leads to Romeo’s banishment. Juliet’s parents, rather than respecting her free will and her true feelings, work against her and force her into what she believes is a hopeless situation. Juliet, constrained by her society, is unable to stand up for her love of Romeo, she lies when she accepts her parents’ demands to marry Paris. In a sense, society fails when the letter from the friar to Romeo is not delivered, which would inform Romeo of the ploy to save the young couple. Friar Laurence plays an integral and yet morally ambiguous role in the play. The friar respects and acknowledges the love between Romeo and Juliet when he agrees to secretly marry them. However, by doing this in secret, he subverts the established secular order. In the end, rather than mediating from his position of religious authority, the friar devises a secretive plan that goes wrong and leads to the death of the young lovers.

Love is so powerful for Romeo and Juliet because it takes on spiritual dimensions. Romeo mentions that he will be “new baptized” by their meeting and claims that his love for Juliet is

actually “my soul that calls upon my name.” Juliet acknowledges the “infinite” qualities inherent in her feelings. Love, or the “religion of mine eye,” as Romeo has called it earlier, creates powerful forces in each. Juliet acknowledges that “God joined my heart and Romeo’s.” When Romeo is banished from the city for killing Tybalt, he claims to the friar that banishment is worse than death because it would be banishment away from Juliet. Again, Romeo seems to be mixing religious feelings with his feelings of love for Juliet. He states that his banishment would be “purgatory, torture, hell itself” and that “Heaven is here, where Juliet lives.” In the Biblical sense, hell is the absence of God, while for Romeo, hell now becomes the absence of love as he has mixed his spiritual longings with his romantic ones. The death of the lovers occurs in a vault, and although the lovers themselves fail to resurrect, as was the friar’s plan, a new peace is brought with the reconciliation of the warring families.

Source:

Douglas Dupler, Critical Essay on Romeo and Juliet, in Drama for Students, Thomson Gale, 2005:

Stopford A. Brooke

In the following excerpt, Brooke argues that the feud between the families is the central event in Romeo and Juliet, stating that the play depicts the process by which “Justice” achieves harmony and reconciliation through the sacrifice of the innocent lovers.

In the first four scenes [of Romeo and Juliet], so long and careful is (Shakespeare’s] preparation, all the elements of a coming doom are contained and shaped—the ancient feud, deepening in hatred from generation to generation, the fiery Youth-in-arms of whom Tybalt is the concentration, the intense desire of loving in Romeo, which thinks it has found its true goal in Rosaline but has not, and which, therefore, leaps into it when it is found in Juliet; the innocence of Juliet whom Love has never touched, but who is all trembling for his coming; the statesman’s anger of the Prince with the quarrel of the houses, and finally, the boredom of the people, whose quiet is disturbed, with the continual interruption of their business by the rioters—

Clubs, bills, and partizans! Strike! beat them down! Down with the Capulets, down with the Montagues !

[I. i. 73-4]

a cry which seems to ring through the whole play. It is impossible this should continue. Justice will settle it, or the common judgment of mankind will clear the way.

The quarrel of the houses is the cause of the tragedy, and Shakespeare develops it immediately. It begins with the servants in the street; it swells into a roar when the masters join in, when Tybalt adds to it his violent fury, when the citizens push in—till we see the whole street in multitudinous turmoil, and the old men as hot as the young…. Then, when the Prince enters, his stern blame of both parties fixes into clear form the main theme of the play. He collects together, in his indignant reproaches, the evils of the feud and the certainty of its punishment. We are again forced to feel that the overruling Justice which develops states will intervene. (pp. 35–6)

[By the end of Romeo and Juliet, Justice] has done her work. She has passed through a lake of innocent blood to her end. Tybalt, Mercutio, Paris, Romeo, Juliet, Lady Montague, have all died that she might punish the hate between the houses. Men recognize at last that a Power beyond them has been at work. ‘A greater power,’ cries the Friar to Juliet, ‘than we can contradict hath thwarted our intents’ [V. 111. 153–54]. The Friar explains the work of Justice to the Prince; the Prince applies the punishment to the guilty

C

Where be these enemies? Capulet! Montague! See what a scourge is laid upon your hate, That heaven finds means to kill your joys with love; And I, for winking at your discords too, Have lost a brace of kinsmen; all are punish’d.

(V. iii. 291-95)

O

The reconciliation follows. That is the aim of Justice. The long sore of the state is healed. But at what a price? We ask, was it just or needful to slay so many for this end? Could it not have been otherwise done? And Shakespeare, deeply convinced, even in his youth, of the irony of life, deeply affected by it as all his tragedies prove, has left us with that problem to solve, in this, the

first of his tragedies, and has surrounded the problem with infinite pity and love, so that, if we are troubled, it may be angry, with the deeds of the gods, we are soothed and uplifted by our reverent admiration for humanity.

Shakespeare could not tell, nor can we, how otherwise it might have been shaped; but to be ignorant is not to be content. We are left by the problem in irritation. If the result the gods have brought about be good, the means they used seem clumsy, even cruel, and we do not understand. This is a problem which incessantly recurs in human life, and as Shakespeare represented human life, it passes like a questioning spirit through several of his plays. I do not believe that he began any play with the intention of placing it before us, much less of trying to solve it. But as he wrote on, the problem emerged under his hand, and he became aware of it. He must have thought about it and there are passages in Romeo and Juliet which suggest such thinking, and such passages are more frequent in the after tragedies. But with that strange apartness of his from any personal share in human trouble, which is like that of a spirit outside humanity-all the more strange because he represented that trouble so vividly and felt for it so deeply-he does not attempt to solve or explain the problem. He contents himself with stating the course of events which constitute it, and with representing how human nature, specialized in distinct characters, feels when entangled in it.

This is his general way of creating, and it is the way of the great artist who sets forth things as they are, but neither analyzes nor moralizes them. But this does not prevent any dominant idea of the artist, such as might arise in his imagination from contemplation of his subject, pervading the whole of his work, even unconsciously arranging it and knitting it into unity. Such an idea seems to rule this play. It seems from the way the events are put by Shakespeare and their results worked out that he conceived a Power behind the master-event who caused it and meant the conclusion to which it was brought. This Power might be called Destiny or Nemesis/terms continually used by writers on Shakespeare, but which seem to me to assume in his knowledge modes of thought of which he was unaware. What he does seem to think is; That, in the affairs of men, long-continued evil, such as the hatreds of the Montagues and Capulets or the Civil Wars in England, was certain to be tragically broken up by the suffering it caused, and to be dissolved in a reconciliation which should confess the evil and establish its opposite good; and that this was the work of a divine Justice which, through the course of affairs, made known that all hatreds—as in this case and in the Civil Wars—were against the Universe. We may call this Power Fate or Destiny. It is better to call it, as the Greek did, Justice. This is the idea which Shakespeare makes preside over Romeo and Juliet, and over the series of plays which culminates in Richard III. (pp. 63–5).

[In] Romeo and Juliet the work of Justice is done through the sorrow and death of the innocent, and the evil Justice attacks is destroyed through the sacrifice of the guiltless. Justice as Shakespeare saw her, moving to issues which concern the whole, takes little note of the sufferings of individuals save to use them, if they are good and loving, for her great purposes, as if that were enough to make them not only acquiescent but happy. Romeo and Juliet, who are quite guiltless of the hatreds of their clans and who embody the loving-kindness which would do away with them, are condemned to mortal pain and sorrow of death. Shakespeare accepted this apparent injustice as the work of Justice; and the impression made at the end upon us, which impression does not arise from the story itself, but steals into us from the whole work of

Shakespeare on the story, is that Justice may have done right, though we do not understand her ways. The tender love of the two lovers and its beauty, seen in their suffering, awaken so much pity and love that the guilty are turned away from their evil hatreds, and the evil itself is destroyed. And with regard to the sufferers themselves, there is that-we feel with : Shakespeare—in their pain and death which not only redeems and blesses the world they have left, but which also lifts them into that high region of the soul where suffering and death seem changed into joy and life. (pp. 67–8)

Source:

Stopford A. Brooke, “Romeo and Juliet,” in On Ten Plays of Shakespeare, Constable, 1925, pp. 35–70.

Professional homework help features

Our Experience

However the complexity of your assignment, we have the right professionals to carry out your specific task. ACME homework is a company that does homework help writing services for students who need homework help. We only hire super-skilled academic experts to write your projects. Our years of experience allows us to provide students with homework writing, editing & proofreading services.

Free Features

Free revision policy

$10Free bibliography & reference

$8Free title page

$8Free formatting

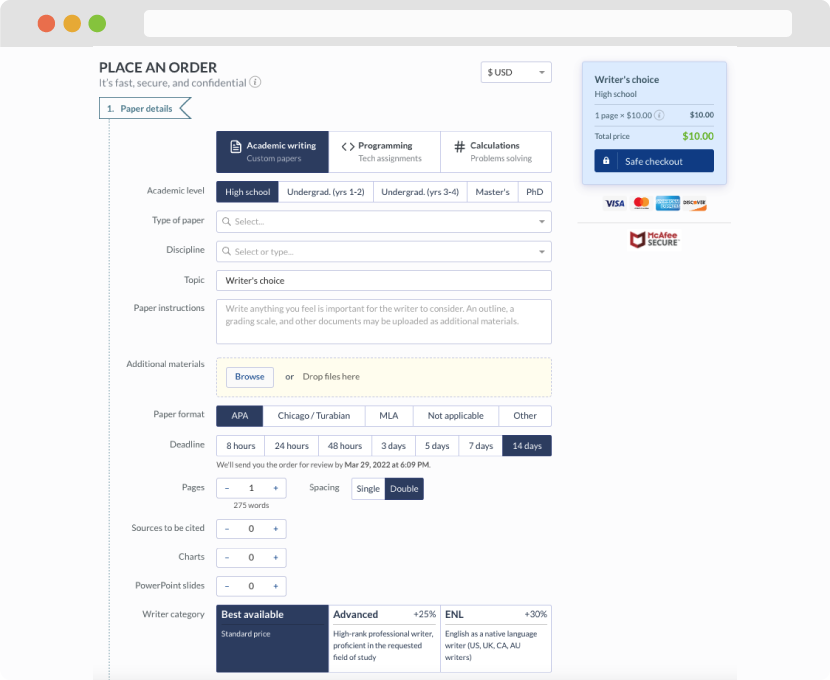

$8How our professional homework help writing services work

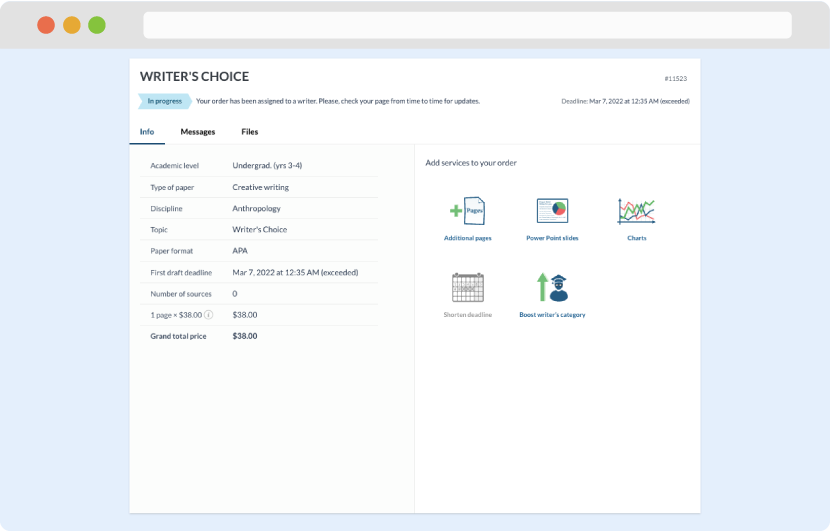

You first have to fill in an order form. In case you need any clarifications regarding the form, feel free to reach out for further guidance. To fill in the form, include basic informaion regarding your order that is topic, subject, number of pages required as well as any other relevant information that will be of help.

Complete the order form

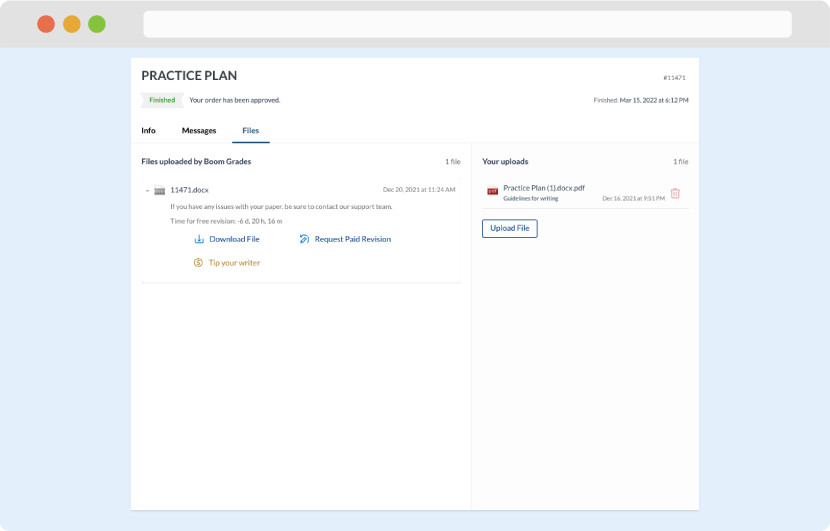

Once we have all the information and instructions that we need, we select the most suitable writer for your assignment. While everything seems to be clear, the writer, who has complete knowledge of the subject, may need clarification from you. It is at that point that you would receive a call or email from us.

Writer’s assignment

As soon as the writer has finished, it will be delivered both to the website and to your email address so that you will not miss it. If your deadline is close at hand, we will place a call to you to make sure that you receive the paper on time.

Completing the order and download