this is instruction:

INTRODUCTION

The main task of a student in ENG 201 is to write the papers for the course. Without handing in these papers you cannot receive a passing grade.

You are required to write four papers for ENG 201:

● Three five page papers, and:

● One ten page paper with a research component.

You will be writing approximately one paper per month of the class. FORMAT

Student papers in ENG 201 are written in MLA format.

What is MLA format?

MLA format is the form for writing your papers. There are rules that you have to obey in order to conform to MLA format. The Modern Language Association (or MLA) makes these rules. Every few years they meet at an MLA convention to review them and, every so often, change and/or modify them.

There are a number of books available on MLA format. If you are curious you might want to think about buying one of them – or at least taking one out from the library.

In addition to this, if you Google the words “OWL” and “Purdue” you will be led to the Online Writing Lab at Purdue University, the best, most authoritative website available on the subject of MLA format. This website is capable of answering almost every conceivable question that you might have on the subject of MLA format.

Keep in mind that if you learn nothing in this class except how to write a college paper in proper MLA format, you will have learned something that you will be using in every class you take from now on – no matter how far you go in your education.

What are the main rules of MLA format?

1) Everything in an MLA format paper is double-spaced.

2) Nothing in an MLA format paper is more than one line away from anything else.

3) All MLA papers contain a header and page number. It is located in the upper right-hand cornerofthepage. Theheaderandpagenumbershouldbeinthesamefontandfontsizeas the body of your paper. The two most acceptable fonts are Times New Roman and Arial. I suggest that you use Arial. The only acceptable font size is 12 point. Everything in your paper (with the exception of footnotes, which you probably will not be using) should be in a 12 point font.

This is how you put in a header and page number:

● Gouptothetopofthe

● Then below that, on the

● Click on “Top of Page.”

● From the options you’re

● That should put the page number on the upper right-hand corner of your screen. But you’re not done yet.

● Then hit the space bar.

● Type in your last name. Then hit the space bar again.

● It should look like this: Smith 1

● If it does, then highlight your name and the page number.

● Click back on “Home”

● Change the font and font size to Arial 12 point.

● Once you’ve done that, you have a header and page number that looks the way it

should look.

4) In addition to this, there is certain information that should be contained, double spaced, in the upper left-hand corner of your paper:

● Your name

● The instructor’s name.

● The class

● The date

When you print the instructor’s name it is always like this: “Professor Smith.” Do not include the first name. And make sure you spell the professor’s last name correctly. They don’t like it when you don’t.

When you print the class, make sure that you add the section number. For example, for this particular class it’s not just ENG 201. It is either ENG 201-2001 or ENG 201-2200, depending on which section you’re enrolled in

There are various ways of printing the date, but I prefer the simplest: Month, Day, and Year, all spelled out: December 10, 2019.

(And don’t include the bullet points.) WHAT NOT TO DO IN AN MLA FORMAT PAPER

screen and click on “Insert.”

right side of the screen, click on “Page Number.

given, click on number 3.

In addition, there are some things that you should definitely not do in an MLA format paper:

1) Do not put a cover page on your paper. It doesn’t need one. All of your relevant information, in proper MLA format, should be on the first page of your paper.

2) Do not place your paper in any kind of fancy binder. It is not necessary. One staple in the upper left-hand corner will do. Make a point of handing in your paper already stapled. You’d be surprised how many students do not. Invest in a stapler. You will use it for every paper in every class you take from now on.

3) College papers should not contain any visual aids whatsoever. Do not include photographs, cartoons, charts, graphs or anything else of that nature in your paper.

4) Do not bold, underline or italicize the title of your paper. It should be in the center of the page, one line below the date and one line above the first line of your text. It should be in the same font and font size as the body of the text (you’d be surprised how many students make their title three times larger than the font of the rest of the paper – don’t do it). Nothing should be either bolded or underlined in your paper. The only exception to this rule would be if you are quoting a piece of writing that contains either bolding or underlining.

YOUR OPENING PARAGRAPH

They say that first impressions count. They count when you’re writing papers for an English class as well. And apart from the impression you give by the format of your first page as a whole, the first impression your professor will have on your paper will come from your opening paragraph.

Your opening paragraph will contain your thesis statement. The thesis statement contains the main idea that your paper is trying to convey. It is of vital importance to the successofyourpaper. Unfortunately,wheremostofmystudentsareconcerned,theopening paragraph tends to be the weakest part of their paper.

So what is a thesis statement? And what makes a good opening paragraph?

THESIS STATEMENT

Your thesis statement is what your paper is about. It is the argument you are making; it is what you are trying to prove in your paper. The thesis statement is in the first paragraph. Usually not the first sentence, it is most often in the middle or the end of the paragraph.

Let’s look at an imaginary opening paragraph:

Critics and readers for almost a century have seen The Great Gatsby as everything from a satire of the excesses of the Roaring Twenties to a tragedy about the death of the American Dream. But a closer look at F. Scott’s Fitzgerald’s novel reveals a more subversive intent on the part of the author: in limning the story of an idealist whose life is destroyed by the reckless Southern belle he’s obsessed with, Fitzgerald, whose Southern belle wife had cheated on him with a French aviator while he was writing the novel, is offering a coded critique of his own troubled marriage.

What is the thesis statement? That Fitzgerald used his novel to explore the nature of his own difficult marriage to a Southern belle (you should be aware, however, that some professors might be very chary of you using an overtly biographical interpretation in your paper, and will prefer that you adhere as closely as possible to the text).

Now, is this thesis statement true? Not necessarily. Does it matter? Yes and no. The point is that having a strong thesis statement makes the writing of your paper easier. It helps you to focus. So if that’s your thesis statement, you can focus your reading on passages in the novel that might appear to back up your thesis (and you can use fancy, graduate student-type words like “limning”).

I’m tempted to say that it almost doesn’t matter what your thesis statement is, provided that you have one, but that’s not true. I had a student once who wrote a paper on Antigone and his thesis statement was contained in the title of his paper: “Creon was a Great King.” Now, more than 2,500 years of explication and criticism of Antigone have all come to the opposite conclusion: that Creon was a terrible king, and that his inability to bend or listen to reason and admit he’s wrong dooms not only Antigone, but Creon and his entire family. So to claim that Creon was a great king is a little silly. More than a little silly, actually.

That doesn’t mean that you can’t express a heterodox opinion in your thesis statement, but it does mean that it would probably take someone with a lot more experience than you have writing academic papers to pull it off successfully. Save that for when you get to graduate school.

THINGS TO AVOID IN YOUR FIRST PARAGRAPH

Be very careful how you introduce the title and the author of the reading about which you are writing. Far too many students open their papers like this: “In the short story “Indian Camp,” written by Ernest Hemingway …” And then they will begin their second paragraph with: “Later on in the short story “Indian Camp,” written by Ernest Hemingway … “

What’s wrong with this? Well, for one thing it’s clunky and boring and is guaranteed to cause my eyes to go rolling back in my head. Go back a page and look at my imaginary opening paragraph for a paper on The Great Gatsby, and see how deftly I introduce the title, the author’s name and the fact that it’s a novel.

Remember that in an English class like this one you’re actually reading two texts at once: the written text your paper is being written about, and the professor for whom your paper is being written. When you are writing a paper for a college class you are writing for an audience of one: the professor. Ask yourself: what does this person want from me? And how can I give it to them so that I can get the best grade possible?

You need to know your professor. But not all professors are alike. They don’t stamp us out with cookie cutters (although it might seem that way sometimes). Some, like me, are sticklers for MLA format. Others don’t particularly care. What will impress one professor will leave another cold. So it’s important to study your professor and figure out exactly what they want from you in terms of your papers so that you can give them exactly what they want. That’s how you get a good grade.

So, with that in mind, how can we rewrite our first mention of the title and author of our reading in order to make it more interesting? What does a good first paragraph look like?

A GOOD FIRST PARAGRAPH

The following is an actual first paragraph from a paper by one of my students:

Both Irwin Shaw’s “The Girls in Their Summer Dresses” and Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants”, while retaining entirely distinct voices, share many similarities beyond their short story format. Deftly dropping the reader into domestic dramas already underway, the reader feels he has voyeuristically been given a front-row seat to what innocuously appear to be two couples at the height of their romantic alliances, only to have this facade chipped away until it is clear we are in fact witnessing their gradual dissolution. I will explore how these stories share many identical themes, use similar story-telling techniques, and even share symbolic physical props.

This paragraph does what a good opening paragraph should do. It’s not perfect: it has some overly fancy writing (“Deftly dropping the reader into domestic dramas” – too much alliteration, too many “d” sounds), which I would have advised the writer to prune back in a rewrite. And it begins with a dubious assertion, that Hemingway and Shaw had “entirely distinct voices,” whereas you can easily detect the influence of Hemingway on Shaw’s prose style in the first paragraph of his story. Nevertheless, it tells you exactly what his paper is about: how in each of these short stories what seems like a casual conversation between a seemingly happy couple is actually depicting the disintegration of their relationship. That’s a thesis statement. And a good one, my perhaps overly picky criticisms notwithstanding.

That having been said, could we make this paragraph better? Keep in mind that, as the old (but true) cliché goes, writing is rewriting. You should never hand in a first draft, although I get the feeling that many of my students do (which goes a long way towards explaining why they get the grades they get). With this in mind, I’m going to do an admittedly presumptuous rewrite of this paragraph to demonstrate how it could be improved.

Irwin Shaw’s “The Girls in Their Summer Dresses” and Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” share several similarities beyond their short story format. Dropping the reader in media res into domestic situations between long-term couples, the reader feels that they have been given a front-row seat to what appear to be two stable relationships, only to have this facade chipped away until it is clear we are in fact witnessing these relationships in the process of disintegrating. I will explore how these stories have identical themes, use similar story-telling techniques, and even make use of nearly identical symbolic physical props.

Compare this to the original. Have I made it better? And if so, how? Is it clearer? More concise? Less fancy? But with all that, is the essential idea of the paragraph still there?

(In media res is a Latin term that goes back to classical antiquity, meaning to drop the reader in the middle of the story instead of going all the way back to the beginning. This is what Homer does in The Iliad. Foreign terms like this should be used sparingly, but when you do use them, they are italicized.)

OTHER THINGS TO AVOID IN YOUR FIRST PARAGRAPH

Do not put the author’s date of birth in the first paragraph of your paper. It’s lazy and boring and frankly I really don’t care when the writer was born. It’s irrelevant, and all

it tells me is that you looked the author up in Wikipedia. Try to come up with something more interesting than their date of birth for your opening paragraph.

Avoid hyperbole, or what I like to call “empty praise.” Do not spend your first paragraph telling me what a great writer this writer is or how this book is the greatest book ever. So avoid at all cost putting a sentence like this in the first paragraph of your paper:

th

“Ernest Hemingway was the greatest writer of the 20 Century,” or “On the Road is the

greatest American novel.” You are not even remotely qualified to make such critical assessments at this stage of your education. Avoid making them altogether.

Avoid sweeping generalizations. It is always a mistake to make sweeping generalizations.

Remember that you are writing an English paper. Not a History paper or a Sociology paper or a Psychology paper or a Gender Studies paper or any other kind of paper. What do I mean by this?

For example, when my students write about The Boys in the Band, a play about a gathering of gay men in New York in the 1960s, far too often they will begin their papers with words to the effect of: “It was very difficult to be a homosexual in the 1960s.” While this is undoubtedly true, it is not the opening sentence of an English paper. Your job is to discuss the play as a play, not as a sociological document about the plight of gay men in the 1960s.

So what would be a good opening sentence for a paper on The Boys in the Band? It would go something like this:

In The Boys in the Band, playwright Mart Crowley places a cross-section of gay men in a New York City apartment and sets them in conflict, both with each other and with a mysterious stranger who may or may not share their sexual orientation, in order to depict both the splendours and miseries of gay life in pre-Stonewall America.

Now while that’s certainly not perfect (do you see a thesis statement there?), at least it discusses the play as a play, and not as a sociological document.

SYNOPSIS VS. ANALYSIS

One of the biggest mistakes that my students make in writing their papers is that their papers contain a lot of synopsis and very little analysis.

What do I mean by this?

When you’re writing a paper for an English class, you are in a very real sense an academic and a literary critic – two things you have never been before. Your job is to write about the text, analyse it and come to some interesting conclusion about it. To state a point of view about the text in your opening paragraph and to spend the rest of your paper making an argument that proves that what you said in your opening paragraph is correct.

Analysis consists of making observations about the text. You are investigating the text the way a detective would investigate a crime scene. You are looking for clues in the text that will serve to help corroborate and prove your thesis. Seeing what’s there, and sometimes seeing what’s not there.

Synopsis, on the other hand, is telling us what we already know. It is both unnecessary and redundant. It doesn’t give us any insight into the text at all. You’re just regurgitating the plot.

So what’s the difference between synopsis and analysis? Let me give you some examples, regarding the William Saroyan short story “The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze.”

Here is synopsis:

Saroyan wanders the city in search of work. He has an interview where he tries to get a job but he is told that “there is nothing this morning, nothing at all” (Saroyan 22). He tries some more to get work but there isn’t any. By this time he understands that there is no hope for him and goes to the library and reads Proust before going back to his room, where he dies.

What’s wrong with this paragraph? A lot, actually.

First of all, it assumes that the author (William Saroyan) and the protagonist of the story (who is not given a name) are the same person: they’re not. Now ask yourself: why doesn’t the protagonist of the story have a name? Why is there no mention of any friends and/or family on whom he can call for help? Why is he being portrayed as being totally alone? Where does the story take place? And who is this Proust guy whom he reads in the Public Library? Why is that important? Why did Saroyan bother to place that very specific detail in his story?

Asking questions like these will allow you to dig into the text, and do more than merely recite the plot, which is all the above paragraph does. It does manage to quote the text once (and cite correctly), but it doesn’t really do what a college paper is supposed to do.

So with that in mind, how do we construct a paragraph that actually analyses the story instead of merely reciting the plot? Taking into account the questions about the text that we’ve already asked, the result might look something like this:

Saroyan’s unnamed protagonist is a symbol as much as a character. His anonymity makes him less an individual and more a case history of the problems faced by aspiring artists struggling to survive during the worst of the Great Depression. He tries to get any job he can find that will make use of his abilities as a writer (and is told that “there is nothing this morning, nothing at all”), only to end up at the Public Library, where he spends an hour of his last day on earth reading Proust (Saroyan 22). WhyProust? Whyreadthatparticularbook,asopposedtothethousandsofotherbooks in the library? The answer seems to be that Proust, like the nameless protagonist himself, is a symbol. Marcel Proust was the author of the longest great novel ever written, as well as a man who, having inherited a fortune from his wealthy father, never had to work for a living and could therefore devote himself entirely to his art in a way that the starving protagonist of the story cannot. To read Proust for an hour on the last day of his life, to begin a book he cannot possibly finish, is an act of faith (this from a man who has no official religion and disparagingly refers to Jesus Christ as the “unlover of my soul”) in the importance of art (Saroyan 21). The protagonist of the story, like Proust, sees art as a substitute for religion, so it is only appropriate that he spends an hour worshipping at the altar of literature on the day he is to die.

Is this paragraph perfect? Not particularly. It runs on a little bit too long. In fact, it could be said to be two paragraphs instead of one and should be broken up (you could

begin a new paragraph starting with the sentence “The answer seems to be that Proust …”). But it does what a college paper is supposed to do: it discusses the text and says things about it, as opposed to merely recounting what happens in it. And that is the difference between synopsis and analysis.

QUOTING IN YOUR PAPER

Another mistake that my students make when writing papers for my class is that they fail to adequately quote the text about which they are writing.

Quoting, and quoting well, is important. Adequately quoting the text tells me that you’ve not only read the text, and know what the important passages are, but that you know what passages in the text will serve to buttress your argument. And that is incredibly important.

Your paper has to have an argument, and you have to use the quotes in your paper to further the argument you’re making. Think of yourself as a lawyer trying to convince the jury (namely, your professor) of the truth of your case. The passages you quote are the evidence you are using to make your case and convince the jury of the soundness of that argument.

There are two ways to quote the text in your paper:

1)) If the quotation is less than three lines of text long, it is simply included in the body of your paper, followed by the citation.

2)) But if the quote is longer than three lines, then it becomes an indented quote.

How do you indent a quote?

For some reason that I don’t really understand, it is considerably more difficult doing this on a laptop than on a desktop and I don’t recommend it. Do it on a desktop if you possibly can.

Here is how you do it on a desktop computer:

● Isolate and highlight the passage you are quoting.

● Go to the toolbar and in the middle of the screen you’ll see “Paragraph.” Click the arrow in the corner of that part of the toolbar.

● In the middle of the box that pops up you will see “Indentation,”

● Go to the part where it says “Left” and move the top number until it gets to 1.0. That will indent your quote exactly one inch.

How long should an indented quote be?

Take your index finger and your thumb and spread them apart almost as wide as you can. That’s about the longest an indented quote should be. An indented quote should not start in the middle of page one and only end at the top of page four, although I have had students who have done this (they did not get very good grades).

A good college paper should contain quite a few indented quotes. Maybe not one per page, but something fairly close to it.

CITING IN YOUR PAPER

You need to quote the text in your paper and you need to cite your sources. Citing in a college paper is the difference between scholarship and plagiarism. Keep in mind, if you plagiarize on your paper you will get an F for the paper. You will not be permitted to rewrite the paper. The F will stay an F. Do it again and you will fail the class. You would think that no one would be so stupid as to cheat a second time after having been caught the first time. Well, you would be wrong. It has happened. More than once.

Cite every single time you quote, without exception. A citation consists of the author’s surname and the page number in parentheses (Hemingway 64). That is what a citation looks like. Note that there is no comma after the author’s name. You don’t need one. And the period goes to the right of the citation.

Sometimes you might even want to cite without quoting. Why would you do this?

Say you’re writing a passage in which, without using the exact words of a given writer, you are nonetheless making use of their ideas and their arguments. You’re giving us the gist, if not necessarily their exact words. You’re paraphrasing. In cases like that I would cite the author even if I’m not quoting what they call in Latin the ipsissima verba, or the exact words, just to give the professor a head’s up and let them know that this is where I’m getting this stuff from.

Where do you place your citation? Only cite at the end of a sentence. Never in the middle. If you quote twice in the same sentence, and they are from the same book, the citation should look like this (Hemingway 61, 124). If you’re quoting from two different books in the same sentence, the citation would look like this (Hemingway 64, Fitzgerald 87).

STYLE POINTS — TITLES

Sometimes in your paper you will be italicizing titles. And sometimes you will be using quotation marks. How do you know when to use which?

It’s actually pretty simple. The rules goes something like this:

● Big things get italics.

● Little things get quotation marks. How does this work in your paper?

A novel (such as Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises) would get italics. A short story (such as Hemingway’s “A Day’s Wait”) would get quotation marks.

(And please note that in that last example, both “Day’s” and “Wait” are capitalized. You’d be surprised how many students write papers on that story and refer to it as “A day’s wait.” Pay attention to capitalization in the title of your text.)

● A play (provided that it’s a full-length play) would get italics.

● A one-act play, on the other hand, would get quotation marks.

● An album (such as Abbey Road by The Beatles) would get italics.

● An individual song on that album (such as “Something”) would receive quotation

marks.

RESEARCH COMPONENT

Your final paper has to have a research component. What is a research component?

For your final ten-page paper, in addition to the text about which you are writing, you have to include two additional texts (sometimes known as secondary sources) discussing that text, and you have to reference (or cite) these texts in your paper. These additional texts can be anything from a biography of the author to an academic paper that you find on JSTOR. They should not be Wikipedia or SparkNotes or some random website. In fact, it would be better for you to eschew (or avoid) websites altogether in writing your papers, with only two possible exceptions: OWL at Purdue and JSTOR. The former will help you with formatting, the latter with research. The more serious your research component, and the better the use you make of your sources, the better your grade will be.

How do you find secondary sources?

If you’re a dedicated student, and serious about getting the best grade possible, you can go to the BMCC library and get on one of the computers there. JSTOR is a website primarily for academics and while at least some of their material is available to the general public, and can be accessed from your home computer or laptop, quite a lot of it is still only accessible by computers physically located at academic institutions. So if you look on a BMCC computer, the more stuff you’re likely to find.

So go on JSTOR and type in the name of the author and the text. You should get a list of material about that author and that text. Do not just take the first two items off the menu – they could be book reviews for all you know. Look at the list carefully. Open up some of the readings. Is it a recent academic paper by a professor at a major university? Or is it something a lot less substantial? Is it from the past few years? Or is it from 1939 and badly dated? These things matter. You always want to cite current academic scholarship.

A lot of these papers will begin with what they call an abstract, or a short description of the contents of the paper. Read the abstract. Do you agree with it? Disagree with it? Does it sound like something that you can make use of? If so, print out the article. By the time you’re done looking through JSTOR, you should have a small pile of academic articles to sift through. See which two of those articles fit the purposes of your paper the best. You won’t need the others (although there’s no rule against having more the two sources for your final paper, and it would look impressive).

FINAL THOUGHTS

Start early. Figure out as early as possible in the semester what readings you want to write about. This is especially important for your final paper. The sooner you get started, the more time you will have to find your secondary sources as well as write (and rewrite) your paper and the better it will be when you hand it in.

One of the advantages of starting early is that you will have the luxury, once you’ve completed a draft of your paper, of putting it aside for a day or so — possibly longer than that. Then you can come back to it fresh, look at the hard copy (and you should always make your revisions by hand on the hard copy) and you will see mistakes, both in style and substance, that you didn’t see before. And you can go about improving the argument, and making your paper much better than it was before. As the old cliché goes, good papers aren’t written — they’re rewritten.

Read the reading carefully. More than once. Take notes. Ask yourself questions about the text. Why does the novel start here? Why does it end the way it does? Why does the hero make the kind of choices they make? What could they have done differently that might have changed the outcome?

Think about writing an outline. You are looking to make a logical argument that flows from the first paragraph to the last. It is much easier to see the structure of your argument in an outline.

You want your paper to seem organized and structured, not something that reads as if you’re just making it up haphazardly from paragraph to paragraph. That kind of paper will get you a C if you’re lucky.

Do not use quotation marks in your paper unless you are quoting the author or some other source. It is not “cute” and it is not “amusing.” Don’t do it.

Keep in mind when you are writing your paper that you are discussing imaginary people who have never existed and never will exist except in the mind of the author. Do not write about them as if they are real people about whom you can be judgmental. If you dislike the protagonist of the book, keep it to yourself.

Avoid using expressions like “I think,” “I feel,” “I believe” and “In my opinion” in your paper. Have the confidence to make the statement outright without qualifying it.

Do not under any circumstances use the words “in conclusion” at the start of your final paragraph. It is a college paper, not a high school debate.

Never hand in a first draft. And never hand in a paper that you haven’t printed out and revised by hand multiple times. Print out your paper. Proofread it. Read it aloud. Rewrite it. Print it out again. Proofread it again. Read it aloud again. Rewrite again. Do this over and over and over again and only stop when you have to hand it in.

Good writing is bad writing made better. If your paper gets a bad grade, that just means that you didn’t spend enough time rewriting it. Take a look at what I say about it and start rewriting.

Take the time. Make the effort. Put in the hours and rewrite your paper as often as you have to until it’s as good as you can make it. Be a perfectionist — but get it in on time.

A good paper is a careful paper.

APPENDIX – PAPER CHECKLIST

Before you hand in your paper, go over the following checklist and make sure that you’ve checked off every item on the list.

□ Does my paper have a header and page number?

□ Is my header and page number in the same font and font size as the rest of my paper? □ Is the information in the upper-left-hand corner of my paper correct?

□ Is that information double-spaced?

□ Have I included the section number of the class?

□ Have I spelled the professor’s name correctly?

□ Is everything in my paper double-spaced?

□ Is the title of my paper only one space away from both the date (above it) and the first paragraph (below it)?

□ Is the title of my paper in the same font and font size as the rest of my paper? Not bolded or underlined?

□ Does the text of my paper start only one space away from the title? □ Have I avoided hyperbole (or “empty praise”) in my first paragraph? □ Does the first paragraph of my paper contain a thesis statement?

□ Does the body of my text attempt to prove my thesis statement?

□ Do I quote the text adequately?

□ Do I cite every single time I quote?

□ Do I have indented quotes in my paper?

□ Have I remembered to cite whenever I use someone else’s words in my paper?

□ Have I used italics and quotation marks correctly for titles of works (big things get italics, little things get quotation marks)?

□ Have I quoted the titles of things correctly, capitalizing words that need to be capitalized (that is, “A Day’s Wait,” not “A day’s wait”)?

□ Have I proved my thesis statement by the end of my paper?

□ Does my final paper have a research component?

□ Do I utilize at least two outside sources in my final paper?

□ Do my outside sources help me make my argument and help prove my thesis?

□ Have I used respectable academic sources for my research component, such as I can find on JSTOR, and not Wikipedia or SparkNotes?

□ Have I avoided using expressions like “I think,” “I feel,” “I believe” and “In my opinion” in my paper?

□ Have I spent enough time writing this paper?

□ Have I done enough rewriting on this paper?

□ Am I satisfied that I have done the best possible job I can do on this paper?

Professional homework help features

Our Experience

However the complexity of your assignment, we have the right professionals to carry out your specific task. ACME homework is a company that does homework help writing services for students who need homework help. We only hire super-skilled academic experts to write your projects. Our years of experience allows us to provide students with homework writing, editing & proofreading services.

Free Features

Free revision policy

$10Free bibliography & reference

$8Free title page

$8Free formatting

$8How our professional homework help writing services work

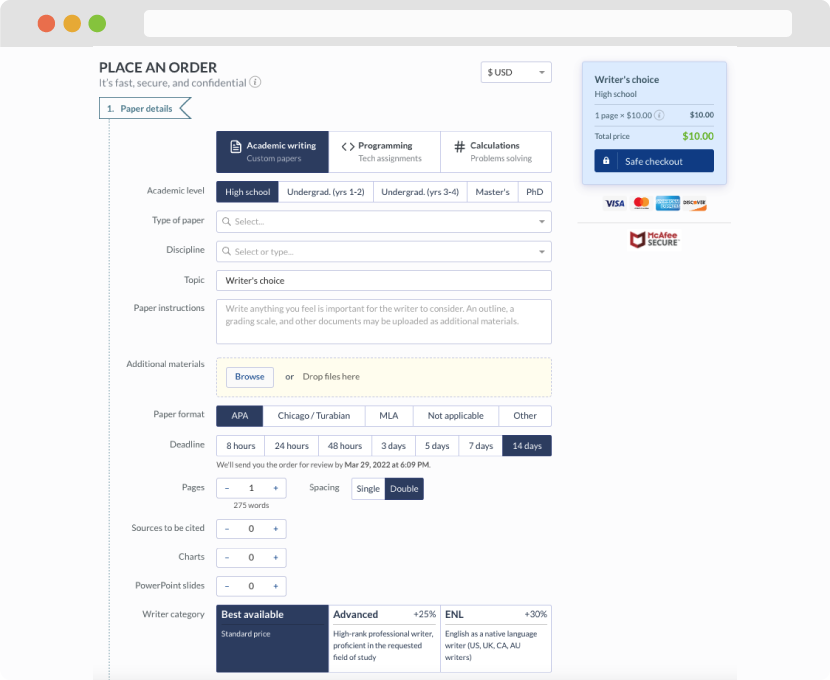

You first have to fill in an order form. In case you need any clarifications regarding the form, feel free to reach out for further guidance. To fill in the form, include basic informaion regarding your order that is topic, subject, number of pages required as well as any other relevant information that will be of help.

Complete the order form

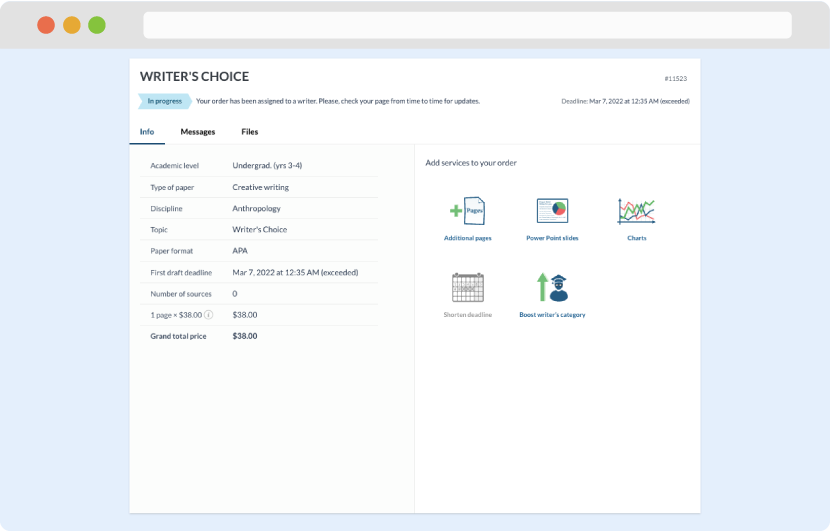

Once we have all the information and instructions that we need, we select the most suitable writer for your assignment. While everything seems to be clear, the writer, who has complete knowledge of the subject, may need clarification from you. It is at that point that you would receive a call or email from us.

Writer’s assignment

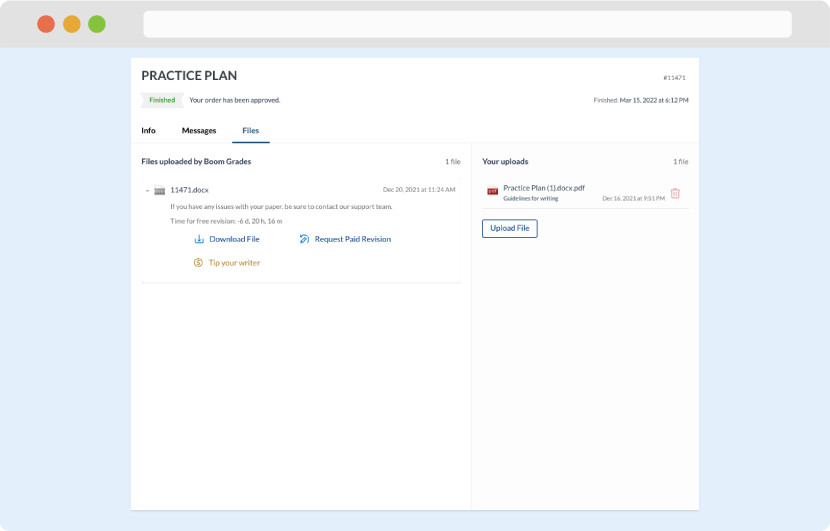

As soon as the writer has finished, it will be delivered both to the website and to your email address so that you will not miss it. If your deadline is close at hand, we will place a call to you to make sure that you receive the paper on time.

Completing the order and download