PBH321: INTRODUCTION TO EPIDEMIOLOGY MAY2020 30069719 [8wk]DiscussionsM3D1: Is it a

M3D1: Is it a cause? Drawing Appropriate Inferences from Findings

Module 3

By the end of this activity, you will be able to discuss the difference between association and causation, and their importance in drawing appropriate inferences.

As your knowledge of epidemiology advances, your ability to draw appropriate inferences from epidemiologic research will do so as well. This is not a skill set that develops overnight, so make sure to remember the difference between an association and causation, and how we evaluate causation in epidemiology.

This week, we’ll begin the discussion by exploring your own reactions to reported associations in the news. Remember that an active discussion is key to an engaging discussion. Be sure to read what others have written and add substantively to the discussion. Time goes fast so start right away!

The first question is based on what you have learned this term so you can engage in discussion immediately.

News stories will sometimes announce a new finding demonstrating an association between a factor and a health outcome. For example, this blurb highlights a finding that drinking wine might be linked to living longer: Do Wine Drinkers Live Longer? Depending On How Much Wine You Consume, You May Be In Luck (Links to an external site.)

What association(s) have you heard of that caught your attention, and did it change your behavior?

For the rest of the discussion, your task is to:

Read the module notes

Friis Text: Chapter 5 pages 103-128 and Chapter 6 pages 129-146

TEXTBOOK; EPIDEMIOLOGY 101 2ND EDITION (2018) ROBERT E. FRIIS

Read the online news clipping about the fictitious town of Epiville, “Epiville Mayor Urges Stork Protection”

After reading, answer the questions one at a time and follow the instructions given below.

What, if any, is the association between the stork population and birth rate?

Using your knowledge of causal criteria, and steps to evaluate an association, how can you best explain the Mayor’s false belief that increasing the stork population would increase the birth rate?

Make the subject line of your post interesting and relevant to its content. This means that you do not simply put “re:” or type in a person’s name that is already clear from the thread. Instead, if you type a full sentence or long enough phrase that the point of your post will be clear. This tip for using the subject line effectively will make navigating all discussion threads easy and meaningful.

Consult the Discussion Posting Guide for information about writing your discussion posts. It is recommended that you write your post in a document first. Check your work and correct any spelling or grammatical errors. When you are ready to make your initial post, click on “Reply.” Then copy/paste the text into the message field, and click “Post Reply.”

To respond to a peer, click “Reply” beneath her or his post and continue as with an initial post.

This discussion will be graded using a rubric. Please review this rubric prior to beginning the discussion. You can view the rubric on the Course Rubrics page within the Start Here module. All discussions combined are worth 35% of your final course grade.

Participation in this discussion addresses the following outcomes:

Describe the difference between association and causation (CO5)

Describe criteria of causality (CO5)

Recognize the role of chance in associations (CO5

During this module you will:

Read:

Required

Module Notes: Association and Causality

Friis Text: Chapter 5 pages 103-128 and Chapter 6 pages 129-146

“Epiville Mayor Urges Stork Protection”

Module 3: Module Notes: Descriptive epidemiology, and associations in epidemology – Part 1

Descriptive Epidemiology

Descriptive epidemiology is the analysis and description of disease patterns by person, place, and time. For example, who is getting the disease? What is their age, sex, religion, race, educational level, etc.? These factors tell us something about who is at risk. We also need to know something about place. Where are rates of disease highest and lowest? The objectives of descriptive epidemiology are to: permit evaluation of trends; provide the basis for planning; and identify problems that can be further studied using analytic methods (aiding in the creation of hypotheses).

For example, what hypotheses can you generate from the patterns observed on this map? This map of the US depicts each county with a color corresponding to the rates of cancer mortality. The color range is from dark blue (lowest rates) to dark red (highest rates).

The image shows a map of the United States including Alaska and Hawaii. Each state has outlines subdividing it into counties. The title of the image is “Cancer mortality rates by county (age-adjusted 1970 US population) for lung, trachea, bronchus and pleura for white males for the years 1970 to 1994. The legend provides information about the rates of mortality per 100,000 population. For the US as a whole, the rate is 69.4 per 100,000. The highest 10% has the range of 91.04 to 150.47 deaths per 100,000. The lowest 10% has the range of 13.17 to 45.11 deaths per 100,000. There are also 43 counties that have sparse information which accounts for 0.01% of deaths per 100,000. The link to the National Cancer Institute at the bottom of the image links to tables with specific data.

Source: National Cancer Institute (Links to an external site.) Atlas of Cancer Mortality in the US.

Plain text file

It looks as if trachea, bronchus, and lung cancer mortality rates are more common in the southeastern areas of the US and least common in the Midwest. This is shown by the darker red areas centered in the southeast, and darker blue in the Midwest. Perhaps smoking rates are higher in these areas? Perhaps there are differences in health care access?

In addition to person and place, we may also consider the frequency of disease over time to assess changes in risk factors. For example, is the present frequency of disease different from the past? How has it changed over time? Remember from the first module where you learned that epidemiology is the study of the distribution and determinations of disease? You can think of descriptive epidemiology as characterizing the amount and distribution of a disease within a population. Analytical epidemiology is concerned with the determinants of disease. You can think of descriptive epidemiology as the “who?”, “where?”, and “when?” Analytical epidemiology is concerned with the “why?” and “how?”

Graphic showing descriptive epidemiology on the left, encompassing the who, when and where questions. While analytical epidemiology is on the right, encompassing the why and how questions.

As an epidemiologist, you will learn to draw inferences from descriptive epidemiology to formulate hypotheses that can be further studied with analytic epidemiologic study designs. There are several primary epidemiologic study designs for testing hypotheses that we will discuss throughout this course.

Person Variables

The “who” question is most commonly answered in terms of age, sex, race, or socioeconomic status (SES). However, other descriptive variables are used such as religion, sexual orientation, country of birth, or marital status (to name a few). Some of these variables will be further explained here.

Age

As you learned earlier, age is an important variable to consider when examining disease. As you know, mortality increases with age, so considering age-specific or age adjusted rates is useful in describing a disease or health condition. However, examining health by age can provide important insights into a disease or health condition. Consider Type II diabetes, which was formerly known as adult onset diabetes. Examining incidence of diabetes by age provided insight into a new trend in early onset Type II diabetes. For example, the graph below shows incidence of diabetes (y-axis), over time (x-axis). The 18 to 44, the 45 to 64, and the 65 to 79 year old age groups are represented by different lines. All lines show an increase over time; incidence among 18 to 44 year olds is lower than the other age groups, but shows an increase over time as well.

Line graph showing the incidence of diagnosed Type 2 diabetes. The title is “Incidence of Diagnosed Diabetes per 1,000 Population Aged 18 to 79 years, by age, United States, the years between 1980 and 2014. There is a description below the title which says “From 1980 to 2014, in adults aged 65 to 79 years, the incidence of diagnosed diabetes nearly doubled from 6.9 to 12.1 per 1,000. In adults aged 45 to 64 years, incidence of diagnosed diabetes showed no consistent change during the 1980s, increased from 1991 to 2002, and leveled off from 2002 to 2014. Among adults aged 18 to 44 years, incidence increased significantly from 1980 to 2003, showed little change from 2003 to 2006, then significantly decreased from 2006 to 2014.” The x axis indicates each year between 1980 and 2014. The y axis indicates incidence per 1,000 population. The legend provide information about the three lines represented in the graph and includes 18 to 44 year olds, 45 to 64 year olds, and 65 to 79 year olds.

Source: Sex Differences Within Race/Ethnicity (Links to an external site.) (California Department of Public Health)

Plain text file

Sex

Sex differences have been shown to be common across many health conditions and diseases. Examining certain diseases without looking at sex-specific measures would provide an erroneous (or confounded) picture of what is happening. For example, see the charts below on age-adjusted deaths rates for unintentional injuries by sex. The image below shows two charts, side by side, one representing death rates by race/ethnicity among males, the other among females. In each chart, a different color line represents a different racial/ethnic group. The charts show that for all racial/ethnic groups, the rate of death is higher among males than females. If these rates were presented as overall rates, one might erroneously infer higher mortality rates for females than is the truth.

Image of two line graphs side by side. Title of the image is Unintentional Injury Age-adjusted Death Rates by Sex and Race including Ethnicity for California, the years 2000 to 2010. The left line graph has a subtitle of male and the right line graph has a subtitle of female. The x axis for both graphs is death rate per 100,000 measured at the following points: 30, 60, and 80. The y axis for both graphs is the years 2000 through 2010, measured in two year increments. The legend for both graphs provides information about each of the four lines and indicates a studied race or ethnicity. The races and ethnicities represented are American Indian, Black, White, Hispanic, and Asian. The highest point on the graph for any race or ethnicity for males is nearly 80 per 100,000 for all years represented. The highest point on the graph for any race or ethnicity for females is about 50 per 100,000 for all years represented. The highest points for both males and females are for American Indians.

Source: Sex Differences Within Race/Ethnicity (Links to an external site.) (California Department of Public Health)

Plain text file

Race/ethnicity

Race/ethnicity as well can be very useful in descriptive epidemiology, as racial/ethnic differences are common across many health conditions or diseases. Take, for example, this figure showing birth rates among teens (y-axis) by race/ethnicity over time (x-axis). Each line represents a different racial/ethnic group. Although rates over time are declining (going from higher to lower as you read left to right) for all racial/ethnic groups, Hispanics and blacks have a much higher birth rate among teens than whites. This figure demonstrates that a large disparity by race/ethnicity still persists.

Image of a line graph and the title is Birth rates for females aged 15 to 19 years. Source: National Vital Statistics System, United States, for the years 2006 to 2014. The x axis shows births per 1,000 females aged 15 to 19 years. The y axis is the years between 2006 and 2014, measured in yearly increments. The legend provides the information about the three lines in the line graph and indicates Hispanic, Black, non-Hispanic, and White, non-Hispanic. The highest point for Hispanic is nearly 80 per 1,000 births in 2006 and has a low point of about 45 per 1,000 births in 2014. The highest point for Black, non-Hispanic is just over 60 per 1,000 births in 2006 and has a low point of 40 per 1,000 births in 2014. The highest point for White, non-Hispanic is about 36 per 1,000 births in 2006 and has a low point of about 20 per 1,000 births in 2014.

Source: CDC MMWR: Reduced Disparities in Birth Rates Among Teens Aged 15–19 Years — (Links to an external site.)

United States, 2006–2007 and 2013–2014 (Links to an external site.) (Romero, et al.)

Plain text file

Socioeconomic status (SES)

SES can be measured in a variety of ways, but the aim is to measure one’s position in society. Most comprehensively, SES is a composite of one’s income, education, and occupation. However, all three are used as proxies when all information is not available.

Module 3: Module Notes: Descriptive epidemiology, and associations in epidemology – Part 2

Place

Place as an important variable in descriptive epidemiology cannot be underscored enough. Any health issue or disease you can think of will have variation by place. Variation can arise in comparing different countries, different states or localities within countries, or even different sections of the same locality (urban vs. rural). Looking at Lyme disease for example, this map clearly shows “where” this disease is of concern, and where we might start to focus new efforts. The map below is a map of the United State where cases of Lyme Disease are displayed as a blue dot. Higher concentrations of cases look like dark blue areas. Lyme Disease is heavily concentrated in the Northeast, but the map shows cases popping up in mid-West.

Click image to enlarge

The image shows an outline map of the United States, including Alaska and Hawaii. The title of the map is “Reported Cases of Lyme disease in the United States in 2014.” A note on the bottom of the image states “one blue dot is placed randomly within county of residence for each confirmed case.

Source: CDC Lyme Disease Maps (Links to an external site.) (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015)

Time

Time can show us changing trends over a long period of time (secular trends), or within a short period of time (seasonal trends). Think about influenza which has a strong seasonal pattern. Knowing the peak months of flu activity assists in better preparing the public and health professionals. The graph below shows the months of the year (x-axis) by the number of times each month was the peak month for influenza from 1982–2014 (y-axis). February is the most commonly the peak month for influenza in this image.

Click image to enlarge

Image of a bar graph. The title is Peak Month of Flu Activity 1982 through 2014. The x axis shows the times when a particular month was a season peak in increments of 2. The y axis shows the months October through May.

Source: CDC: The Flu Season (Links to an external site.) (Center for Disease Control and Prevention)

Later in the course we will discuss outbreak investigations. Outbreak investigations initially rely heavily on descriptive epidemiology. A classic example of descriptive epidemiology is the creation of an epidemic curve, or epi curve, in which cases are plotted by time to help in hypothesis generation. You will also learn more about epi curves in throughout this course. The figure below is a graph showing an outbreak of Salmonella by state of residency. Date of illness onset is on the x-axis, and number of ill cases is on the y-axis. Cases are plotted over time, and presented as either residents of Washington, or not. This particular epi curve is useful in that it provides information about a disease in terms of time, and place.

Click image to enlarge

The image shows a bar graph. The title is “Date of illness onset among 192 persons infected with the outbreak strains of Salmonella 4,[5], 12:i:- or S. Infantis, by state residency status for Washington in the year 2015.” The x axis shows the number of ill persons, in increments of 2. The y axis shows the date of illness onset and is in increments beginning April 25th and ending October 10th. The legend provides information about Non-Washington state residents and Washington state residents. The highest peak of number of ill persons was about 19 which occurred for Washington state residents around July 19. Low points occur on both ends of the curve, with 1 case reported on April 25 and one case reported on October 4 or 5.

Source: CDC: Notes from the Field: Outbreak of Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella Infections Linked to Pork — Washington, 2015 (Links to an external site.) (Kawakami et al., 2016)

Plain text file

Time to check your understanding! Unlike the two previous modules, you will be going to the Check Your Understanding link found in the Table of Contents in this module. When you are finished, you can return to these module notes.

Association and Causality

Over the last 2 modules, you have been learning more about the study of epidemiology, and how we measure health conditions or diseases. You might have started questioning what conditions or factors might cause a health condition or disease to occur. Before getting into how we study these questions, you will be introduced to the concept of association, the criteria of causality, the role of chance in associations and how they are all used in drawing epidemiologic inferences from analytic studies. By gaining a foundational understanding of the difference between association and causation, you will be ready to interpret findings from the study designs you will learn about in Modules 4 and 5.

Module 3: Module Notes: Descriptive epidemiology, and associations in epidemology – Part 3

Associations

First let’s discuss what a cause is. Rothman and Greenland say that a cause is “an event, condition, or characteristic which precede disease and without which the disease would not occur”(Rothman & Greenland, 2005). A cause is different from a risk factor, which is a behavior, characteristic, or exposure that is known to be associated with a disease. A risk factor may be a cause for a disease, but it may not. In other words, a disease might vary in relation to a risk factor, but that risk factor might not be the cause of the disease.

So what is an association? Let’s start with an example. Say you are interested in knowing if exercise has an impact on life expectancy. One might assume based on layman knowledge that the more hours a week someone exercises, the longer they will live. Here is a graph depicting this relationship.

Image of a line graph and the title is “Years of life gained after age 40.” The x axis shows years of life gained and has increments of one year between 0 and 5. The y axis shows leisure time physical activity (MET-hours per week). There is an upward curve starting at 0, 0 (x and y axis points) and ending at 4.5 and 27 (x and y axis points respectively). Intersections of the x and y axis are as follows: 0,0. 1 point 8, 4. 2 point 5, 5. 3 point 5, 10. 4, 20. 4 point 5, 27.

Plain text file

You can see here that the more someone exercises, the more years of life are gained. In other words, there is apositive association between the exposure (leisure time physical activity), and the outcome (years of life gained). This example shows how one may graph or plot the relationship between two continuous variables. Continuous variables (Links to an external site.) can have any value between 0 and infinity, for example weight, height, or temperature. Two variables can also be negatively associated with one another. For example, the graph below is a made up example of the association between blood pressure and number of vegetables consumed daily.

Image of a line graph where the x axis shows blood pressure rate and the y axis shows number of vegetables consumed daily. Blue dots indicate blood pressure measurements. A line drawn through the dots shows a decline. The peak blood pressure reading is 150 and located at 1 vegetable consumed daily, to a low point reading of blood pressure at 115 and located at 15 vegetables consumed daily.

Plain text file

In this graph, the number of vegetables are on the x-axis, and blood pressure is on the y-axis. The graph shows higher blood pressure among people who consume fewer vegetables daily, and lower blood pressure among people who consume more vegetables daily. This is a classic example of what a negative association looks like; as one variable increases, the other decreases. When examining scatterplots, looking at a trend line can be quite useful in interpreting the direction of the association; a trend line that slopes down, as in the example above, shows a negative association, a trend line that slopes up (as in the previous example) shows a positive association.

There can also be no association at all. See the below example of Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) scores and one’s grade point average (GPA).

Image of a graph that depicts data points scattered across the chart. The x axis is GPA (Grade Point Average) and runs from 1 point 5 to 4 point 0. The y axis is SAT (Scholastic Aptitude Test) scores and runs from 500 to 1400. There is a dashed line drawn across the middle of the graph, right around the GPA of 3 point 0.

Source: Preston, 2004

SAT score is on the a-axis, and GPA is on the y-axis. A trend line is provided showing a relatively straight line across, in the midst of very scattered marks. Unlike a sloping trend line that shows a positive or negative association, a straight trend line usually indicates no association. This graph is showing that there is no clear association (positive or negative) between the two variables; you can not conclude that SAT scores either increase or decrease with increasing GPA.

What if you have two categorical variables you want to study the association between? Categorical variables can only take on specific values that are limited to a category. For instance, let’s look at gender, and if one has cancer or not. Are women more likely to get lung cancer than men? You cannot use a scatterplot like you can with two continuous variables. Instead, epidemiologists use what is called a contingency table, or a 2×2 table. This type of data presentation is used for some analytic studies we will discuss later on (case-control, cohort, and cross sectional studies). A 2×2 table is made up of four quadrants, A, B, C, and D.

A= the number of people in which the exposure and the outcome are present

B= the number of people in which the exposure is present but the outcome is absent

C= the number of people in which the exposure is absent but the outcome is present

D= the number of people in which neither the exposure nor the outcome are present

Outcome status

Outcome- Present Outcome-Absent Total

Exposure-Present

A B A+B

Exposure-Absent

C D C+D

Total

A+C B+D A+B+C+D

When thinking of a potential association between two dichotomous outcomes, it’s useful to think in terms of proportions. One would assume that if an exposure was associated with an outcome, a higher proportion of persons with the exposure would have the disease than persons without the exposure. Take a look at this graphical representation of the association between two categorical variables: pregnancy and breast cancer.

The image is a bar graph. The x axis shows percentages of breast cancer and the y axis shows two comparison points – never pregnant and pregnant at least once.

Outcome status

Exposure status

Breast cancer No breast cancer Total

Never pregnant

75 10 85

At least one pregnancy

9 15 24

Total

84 25 109

75 out of 85 women who had never been pregnant have breast cancer, or 75/85=88%

9 out of 24 women who had at least one pregnancy have breast cancer, or 9/24=38%

A higher proportion of women who have never been pregnant have breast cancer than women who have had at least one pregnancy. This finding might be suggestive of an association between the exposure and the outcome. An epidemiologic measure can be calculated from these two proportions to quantify the level of association. You will learn more about using contingency tables, and how to measure associations using a contingency table in the next module.

Module 3: Module Notes: Descriptive epidemiology, and associations in epidemology – Part 4

Criteria of Causation

Just because an exposure and an outcome are associated, it does not necessitate a causal relationship (i.e association does not mean causation).

Sir Bradford Hill developed a set of nine criteria for assessing causality that have been extensively applied in epidemiology and public health. These criteria are guidelines to help determine if associations are causal, but should not be used as rigid criteria. These criteria can be used as a tool by which we may approach the process of determining if an observed association between an exposure and an outcome is causal.

Hill’s Nine Criteria

Experiment: As you will learn in Module 4, experimental studies provide the strongest evidence of causality because of their ability to control for bias. This means that if an investigator initiates an intervention that modifies the exposure through prevention, treatment, or removal, disease rates should go down.

Coherence: The association does not conflict with current knowledge of natural history and biology of disease.

Example: Cigarettes were not found to cure skin cancer before discovering an association between cigarettes and an increased incidence of lung cancer.

Plausibility: Either a biological or social model exists to explain the association.

Example: Cigarettes contain many carcinogenic substances. Thus, a relationship between cigarette smoking and lung cancer is plausible. Many epidemiologic studies have identified cause-effect relationships before biological mechanisms were identified. For example, the carcinogenic substances in cigarette smoke were discovered after the initial epidemiologic studies linking smoking to cancer.

Temporality: The causal factor must precede the disease in time. That means, that in order for something to cause a disease or outcome, it has to have existed first. For example, if someone started smoking this year, smoking cannot be a cause of one’s lung cancer that was diagnosed five years ago. This is the only one of Hill’s criteria that always applies. Prospective studies, which you will learn about in the next module, do a good job establishing the correct temporal relationship between an exposure and a disease.

Example: A prospective cohort study of smokers and non-smokers starts with the two groups when they are healthy and follows them to determine the occurrence of subsequent lung cancer.

Specificity: A single exposure should cause a single disease. This is a hold-over from the concepts of causation that were developed for infectious diseases. There are many exceptions to this criteria.

Example: Smoking is associated with lung cancer as well as many other diseases. In addition, lung cancer results from smoking as well as other exposures.

Note: When present, specificity does provide evidence of causality, but its absence does not eliminate the possibility of causation.

Consistency: The association is observed repeatedly in different persons, places, times, and circumstances. Replicating the association in different populations, with different study designs, and different investigators gives evidence of causation.

Example: Smoking has been associated with lung cancer in at least 30 studies.

Strength of the association: The larger the association, the more likely the exposure is causing the disease.

Example: Smokers are 9 times more likely to develop lung cancer than non-smokers; Heavy smokers are 20 times more likely to develop lung cancer than non-smokers.

Biological Gradient: A “dose-response” relationship between exposure and disease exists. This means that people who have increasingly higher exposure levels have increasingly higher risks of disease.

Example: Lung cancer death rates increase with the number of cigarettes smoked.

Example: Smoking cessation programs result in lower lung cancer rates.

Analogy: Refers to the idea that an observed association is more likely to be causal if similar to other associations believed to be casual. We determine this by asking the question, “Has a similar relationship been observed with another exposure and/ or disease?”

Example: Effects of thalidomide on the fetus provide analogy for effects of similar substances on the fetus. (Thalidomide, a drug prescribed in the 1950s for treatment of morning sickness, was ultimately determined to cause birth defects).

Though they do not establish causality directly, Hill’s criteria are useful guides for:

Remembering distinctions between association and causation in epidemiologic research;

Critically reading epidemiologic studies;

Designing epidemiologic studies;

Interpreting the results of your own study

We can’t prove causality with statistical tests or checklists (like Hill’s criteria). Causal inference involves judgments and social processes that change over time as our knowledge base expands. Epidemiologists must use all the tools at his/her disposal to come to thoughtful conclusions about causality.

Defining the Role of Chance

What do you think the likelihood is of observing an association just by chance alone? This question can be answered using statistical procedures to decide, though an in depth explanation of these procedures are outside of the scope of this course. But it should be known that an association can be statistically significant (determined to be not due to chance), or not significant (the association might be due to chance).

(View the TranscriptPreview the document [DOCX, File Size 20KB])

When thinking about whether an observed association between exposure and disease is causal, we have to consider whether the relationship is either due to chance (due to random error) and if it is valid (in other words, unbiased or free of systematic error). As you just learned, there are statistical approaches to determine if the association is what we call “statistically significant,” or unlikely to be due to chance alone. Thus, when we observe a relationship between exposure and outcome, we must consider if there are alternative explanations for the observed association. Generally, we cannot visualize causal relationships directly, but instead infer their existence. We cannot “prove” causation, but can create a belief in a causal relationship by demonstrating a causal framework.

Module 3: Module Notes: Descriptive epidemiology, and associations in epidemology – Part 5

Evaluating Epidemiological Associations

Remember that epidemiological studies determine an association between exposure and outcome. Association does not mean causation. Consider the following statement: If the rooster crows at the break of dawn, then the rooster caused the sun to rise. While one can intuitively claim that the rooster does not cause the sun to rise, there is an association between the two.

As you just learned Hill’s causal criteria, and the role of chance, let’s summarize three major characteristics which help determine if a factor is a cause.

Time order: Causes must precede the effect. They may be either proximate to each other in time or distant, but precedence is required.

Direction: Cause leads to effect, but not vice versa.

Statistically significant association: Causes and their effects must occur together and must not be due to chance. This means there must be a statistical dependence between the causal factor and the effect that has been estimated to not be due to chance.

While these are the major criteria, remember that all three can be met, and the association is still not causal. For example, numerous studies have shown high socio-economic status is positively associated with a higher risk of breast cancer. In this example, all three characteristics are met:

Time order: One’s socio-economic status precedes breast cancer

Direction: Breast cancer does not cause socio-economic status (though one could argue that medical bills could affect socio-economic status),

Statistically significant association: Studies have shown a statistical dependence between the two factors.

So why do we not conclude that socio-economic status causes breast cancer? The plausibility of this causal relationship is in question. Why would someone’s education or income cause cancer? It doesn’t, but there are other factors associated with high socio-economic status that do cause breast cancer. Women of higher socio-economic status are more likely to use birth control pills, use hormone replacement therapy, have children at a later age, and have less children. (Susan G. Komen, 2015) You will learn more about factors associated with both the exposure and the outcome in a later module in which we explore threats to validity of studies.

Time to check your understanding! Go to the Check Your Understanding link found in the Table of Contents in this module. When you are finished, you can return to these module notes.

In the next module you will begin your first of two modules on epidemiologic analytical study designs. In these modules you will learn how we study associations between exposures and outcomes, in an effort to determine causes of disease. The next module will focus on experimental, ecological and cross sectional study designs.

References:

California Department of Public Health. Sex Differences Within Race/Ethnicity (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from https://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/ohir/Pages/UnInjury2010RaceSex.aspx

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (10/22/2014). The Flu Season (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/season/flu-season.htm

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015, 11/5/2015). Lyme Disease Maps (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/maps.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (12/1/2015). Incidence of Diagnosed Diabetes per 1,000 Population Aged 18-79 Years, by Age, United States, 1980-2014 (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/incidence/fig3.htm

Kawakami, V. M., Bottichio, L., Angelo, K., Linton, N., Kissler, B., Basler, C., . . . Lindquist, S. (2016). Notes from the Field: Outbreak of Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella Infections Linked to Pork – Washington, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 65(14), 379-381. doi:10.15585/ http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6514a4.htm

Moore, S. C., Patel, A. V., Matthews, C. E., Berrington de Gonzalez, A., Park, Y., Katki, H. A., . . . Lee, I. M. (2012). Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis. PLoS Med, 9(11), e1001335. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001335

National Cancer Institute SEER. Cancer Statistics Fast Stats: Cancer of the Esophagus by Race and Sex (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from http://seer.cancer.gov/faststats/index.php

Rothman, K. J., & Greenland, S. (2005). Causation and causal inference in epidemiology. Am J Public Health, 95 Suppl 1, S144-150. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.059204

Susan G. Komen. (9/23/15). Risk Factors and Risk Reduction: Socio-economic Status (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from http://ww5.komen.org/Breastcancer/Highsocioeconomicstatus.html

Moore, S. C., Patel, A. V., Matthews, C. E., Berrington de Gonzalez, A., Park, Y., Katki, H. A., . . . Lee, I. M. (2012). Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis (Links to an external site.). PLoS Med, 9(11), e1001335. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001335. Retrieved from: http://vlib.excelsior.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=84441975&site=eds-live&scope=site

Preston, S./SUNY Oswego. (2004). Predicting GPA (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from http://www.oswego.edu/~srp/stats/gpa_sat.htm

Rothman, K. J., & Greenland, S. (2005). Causation and causal inference in epidemiology. (Links to an external site.) Am J Public Health, 95 Suppl 1, S144-150. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.059204. Retrieved from: http://vlib.excelsior.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=17713748&site=eds-live&scope=site

Susan G. Komen. (9/23/15). Risk Factors and Risk Reduction: Socio-economic Status (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from http://ww5.komen.org/Breastcancer/Highsocioeconomicstatus.html

Image citations:

(lung cancer map) National Cancer Institute (Links to an external site.). Atlas of Cancer Mortality in the US. Retrieved from http://ratecalc.cancer.gov/ratecalc/archivedatlas/pdfs/maps/

diagnosed diabetes Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). CDC: Incidence of Diagnosed Diabetes per 1,000 Population Aged 18–79 Years, by Age, United States, 1980–2014 (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/incidence/fig3.htm

unintentional injury California Department of Health. (<span style=”border-bottom: 1px dotted black;” title=”no date”>n.d.</span>) Sex Differences Within Race/Ethnicity (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from https://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/ohir/Pages/UnInjury2010RaceSex.aspx

birth rates Romero, <span style=”border-bottom: 1px dotted black;” title=”and others”>et al.</span>, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reduced Disparities in Birth Rates Among Teens Aged 15–19 Years — United States, 2006–2007 and 2013–2014 (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/pdfs/mm6516.pdf

lyme disease Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). Lyme Disease Maps (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/maps.html

flu activity Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Flu Season (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/season/flu-season.htm MN08 salmonella Kawakami, V. M., Bottichio, L., Angelo, K., Linton, N., Kissler, B., Basler, C., . . . Lindquist, S. (2016). Notes from the Field: Outbreak of Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella Infections Linked to Pork – Washington, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 65(14), 379–381. doi:10.15585/ http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6514a4.htm

self check esophageal cancer National Cancer Institute SEER (National Cancer Institute SEER). Retrieved from seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/…/sect_08_esophagus.pdf

physical activity Moore, et al. (2012). Gains in Life Expectancy After Age 40 (Links to an external site.). [Graph] License: CC0 via PLOS Medicine.

blood pressure (Moore et al., 2012)

SAT scores Preston, S. (2004). Predicting GPA (Links to an external site.). [Graph].

2×2 table Created by author, [Graph] no citation.

pregnant breast cancer Created by author, [Graph] no citation.

smart art Created by author, [Graph] no citation.

self check weight gain Created by author, [Graph] no citation.

Professional homework help features

Our Experience

However the complexity of your assignment, we have the right professionals to carry out your specific task. ACME homework is a company that does homework help writing services for students who need homework help. We only hire super-skilled academic experts to write your projects. Our years of experience allows us to provide students with homework writing, editing & proofreading services.

Free Features

Free revision policy

$10Free bibliography & reference

$8Free title page

$8Free formatting

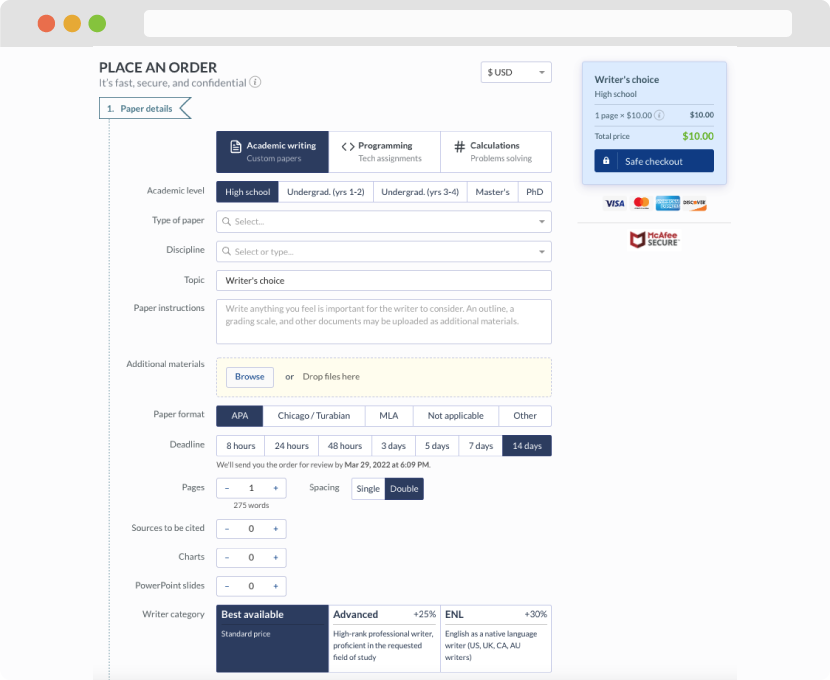

$8How our professional homework help writing services work

You first have to fill in an order form. In case you need any clarifications regarding the form, feel free to reach out for further guidance. To fill in the form, include basic informaion regarding your order that is topic, subject, number of pages required as well as any other relevant information that will be of help.

Complete the order form

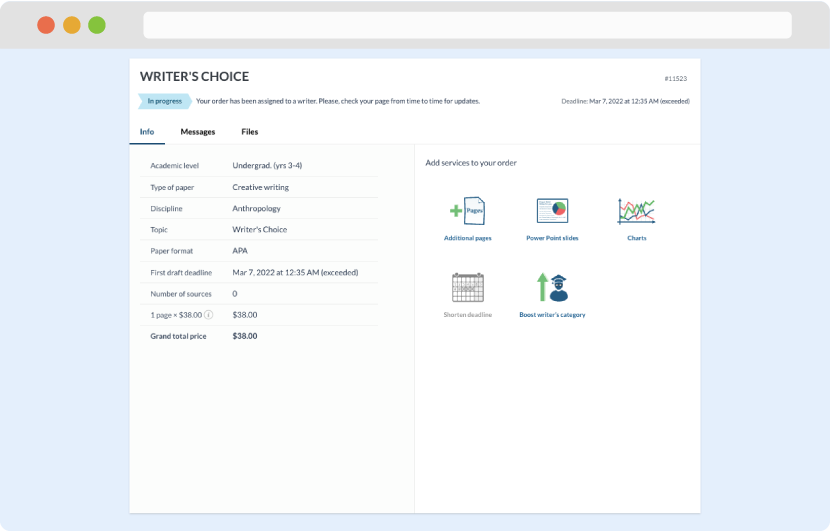

Once we have all the information and instructions that we need, we select the most suitable writer for your assignment. While everything seems to be clear, the writer, who has complete knowledge of the subject, may need clarification from you. It is at that point that you would receive a call or email from us.

Writer’s assignment

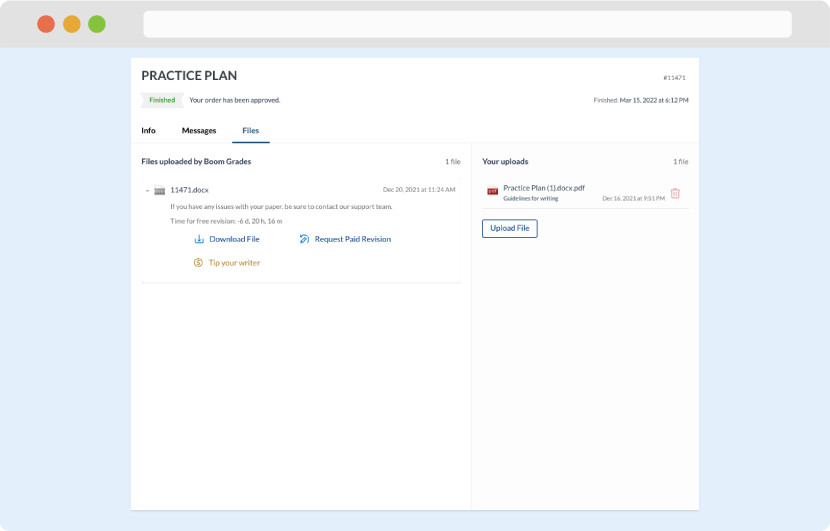

As soon as the writer has finished, it will be delivered both to the website and to your email address so that you will not miss it. If your deadline is close at hand, we will place a call to you to make sure that you receive the paper on time.

Completing the order and download